Architecture, throughout history, has been weighed by a ‘contextual’ magnitude and standardized ‘dimensions’ of length, breadth, depth, or height. The measure of architecture, back then, initialized from the floor and ended at the ceiling, surrounded by the four walls. But, then and now, architectural movements put in new ideas that imbibed enough curiosity to cut across these walls. These are the few significant times when ‘contextuality’, ‘scale’, and ‘space’ were not just dealt with as perceivable terminologies but stood for something more than what met the eye.

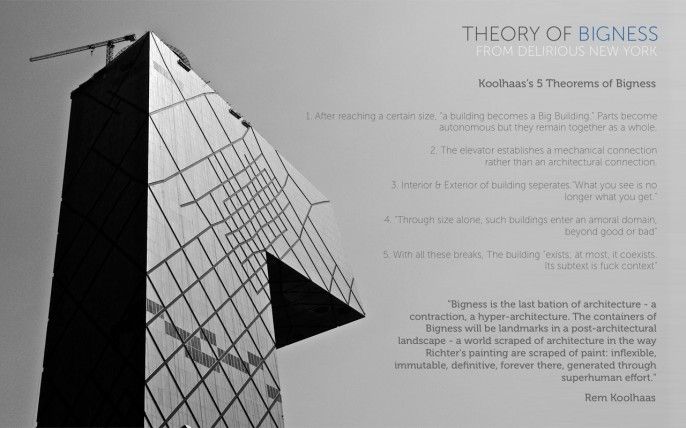

In recent times, the renowned Dutch architect Rem Koolhaas introduced one such concept with his book S, M, L, XL. The idea of ‘Bigness’, which dwells in its pages doesn’t preach to radically “redefine” the scale and measure of architecture, but rather “define it rightly”. Midway through the interview ‘Thinking big’ (by John Rajchman), one is ascertained that S, M, L, XL aren’t chronological and aren’t organized by defined typologies or clustered into public and private projects. Instead, they ascend across various scales and sizes. And going up this ladder, we are introduced to the right idea of ‘Bigness’. ‘Bigness’ is not about the dimensions but rather the ‘parameters’ that the given Architecture stands for.

The idea is to make Architecture stand for something ‘bigger than what the built form’s façade and interior speak of, and everything ‘beyond’ – which one might not be able to see, but can always perceive. A large number of works in practice today are established at a scale, which, by virtue of its dimensions, can very well be categorized as Small or Medium Scale. But there is much beyond the dimensional aspects that define this ‘so-called scale’. Thus, Koolhaas, in his book, re-introduces ‘Bigness’ to throw light on how Man’s need for shelter has evolved down the years, into a desire for Architecture, connecting us to the beyond.

To achieve such a texture of Architecture that breathes within its walls an entire epoch, one must detest ‘contextuality’. The ‘place’ where the building stands, literally, is now obsolete. According to Rem Koolhaas, it is ‘tabula rasa’ or blank slate. So, the idea of a place is either missing or, as we aim for, is infinite. The architecture dictated by ‘Bigness’ jumps off the defined contextual plate. Such a setting is more than liberating in itself. It creates space for ‘tourism’ to thrive – for example, an intermingling of European contextualism and Asian regionalism, performing on the stage of ‘non-contextuality’. Thus, the architecture of one place can very much represent something that is on the other side of the Earth. There is confluence. And then, there is creation. There are no boundaries when there is ‘Bigness’.

The desire for an architectural format that cuts across dimensional scales has shunned and further refined many conventional philosophies. One of them, Koolhaas mentions, is the ‘death of a public space’. This public space, to be true, still exists, in new kinds of sociality and neo-structures of accommodating the ‘collective’. To understand this viewpoint, one can cite the example of a ‘virtual’ privatized public space. Think of a coffee shop – which is a public space, but where people are glued to their own devices, logged into various social networking sites. Conviviality persists here too. So in some form – the public space gets resurrected. When we ‘see’ such a space, we cannot really understand the ‘scale’ of it. Can we? But think of this – the ‘so-called scale’ actually goes beyond that perceived space surrounded by walls and is infinite. There is no contextuality in such a setting; just a pure flow and architectural presence of ‘Bigness’.

The plethora of concepts and repetitive conjecture about ‘Bigness’ leads us to what are the finest contemporary justification and a progressive example – of Pavilion-scale architecture. Technically defining, a ‘Pavilion’ is a light temporary or semi-permanent structure used in gardens and pleasure grounds. A pavilion is in some ways a sculpture with a character of ‘space’. If a story could be knit around the spatial character of the architecture and the aesthetics of a sculpture, the pavilion would be the hero of such a story.

The typology of a pavilion oscillates between that of architecture through function and sculpture through beauty. These have existed as such a typology throughout the history of architecture- from the watchtowers of Chinese dynasties to the Garden Pavilions of the French to the newer and relatively urban Serpentine Pavilions of London.

Pavilions are that unfazed architecture of free spirit that gives a language to the unrestricted expression of an architect, can be used as a platform for innovation in architectural design and construction, or even be a medium for the expression of political, religious, or artistic beliefs. They are the perfect ‘handshake’ of architecture, across different styles, cultures, and even dogmas. A pavilion cannot be compared in scale or in scope to the regular architecture of any scale. Pavilions thus, represent ‘Bigness’ even though they ‘look small’. See the magic of ‘scalability’ in architecture now?

Pavilions go beyond contextuality.

Earlier, there was a time when they acquired permanent settings in the public scape. Today, they are a harbinger to the statement of unrestricted access and freedom of expression. That such condition of temporality and the seamless permeability between the ‘outside’ and the ‘inside’ could be achieved was realized gradually. For example, the display of art could now be detached from conventional permanent settings like museum galleries, and be placed for all to see in pavilions in public space. The dictated ‘place’ has been diffused. The public space, now, is liberated and free. Such a paradigm shift was also to rescue architecture from the implications of the retrofit of structure and services into a building.

This is further accounted for by Achim Menges of ICD Stuttgart noting that ‘Pavilion Architecture’ is the most profound expression of the work of architects because they can be operated as experiments at a ‘testing scale‘ for technologies and fabrications that can potentially be used for the design of actual buildings. Tests as such have led to astonishing results as outer skin thickness reduction to up to a few millimeters, amongst other breakthroughs. MIT has even gone ahead and designed an entire Silk Pavilion using the capabilities of Silkworms on computational scaffolding inputs. Could we perceive pavilions as the ‘perfect playground for progressive architecture’, then?

Pavilions continue to be underestimated in their architectural standing in the public space. They are still often compared in use and importance to buildings that in their long life are able to generate revenue to support the economy. However, positive inspirations can be taken from the likes of the Nehru Pavilion and the Coffee Pavilion in a developing country like India. Another fine example has been set by the 14th Venice Architecture Biennale 2014, directed by Koolhaas himself, which witnessed 65 nations hoping on the pavilion-chariot. Such events put ‘Pavilions’ under the limelight, especially in contemporary landscapes where there seems to have been a resurgence of interest in them.

Copyright 2011 – 2012. All rights reserved. dutchDesign is an undergraduate field school and research program offered by the School of Interactive Arts + Technology (SIAT) at Simon Fraser University in Vancouver, Canada

Rem Koolhaas has long since propagated the belief that scale is a direct influence of the expression of architectural gestures in a building. A pavilion is a pure and truthful rendering of an architect’s imagination that would otherwise be condensed to just concrete frames and restricted layouts as in any building. They continue to surprise, innovate, overwhelm and break the monotony in any and every public contextual setting.

Pavilion-scale architecture is a bold statement on how the book of public space can converge into a size-zero unit of singularity (as a built-form) – and still narrate the story of ‘Bigness’ by pushing the boundaries of content and ideology of architecture in a manner that represents futuristic possibilities in an engaging public experience. It is here where the right measurement of architecture thrives.

By: Sushant Verma, Ankur Podder, and Nivedita Gupta