The core of the built environment is based on ergonomics and the study of the human scale, with the purpose of creating a safe, comfortable and inspiring habitat for mankind. But what happens when the focus shifts towards animals, their natural habitat and their social interactions? When architects and landscape designers became interested in creating architecture for animals is not definite. However, it seems that it all boils down to the zoological park, or “zoo” – a facility where animals are displayed for the public and are bred in captivity.

How can architecture help animals?

Surprisingly, there is evidence that the origins of the modern day zoo are linked to ancient times. In 2009, what appears to be the oldest royal menagerie was found in Hierakonopolis, Egypt, dating back to 3500 BC. while in Mesopotamia, there are records of zoological and botanical gardens, from the 11th century BC. Alexander the Great is known to had captured exotic animals and had them sent to Greece, which had zoos in major cities by the 4th century AD. Similarly, the Roman Empire is known to have kept such animals for study or entertainment. The list goes on with various examples around the world, up to the 16th century AD, when, in 1520, one of the earliest animal collections of the Western Hemisphere, maintained by Aztec emperor Montezuma II, was destroyed by conquistador Hernan Cortes during the Spanish conquest.

Royal menageries continued to exist in Europe, up until the Age of Enlightenment. Some of the most notable ones are associated with Baroque palaces, such as Schönbrunn, Austria, or Versailles, France. As the interest of the European community turns towards government and reason, scientists expand their interest to zoology. Thus, the role and design of the menageries change with the need to study exotic animals in a different environment – one that is more similar to their natural habitat.

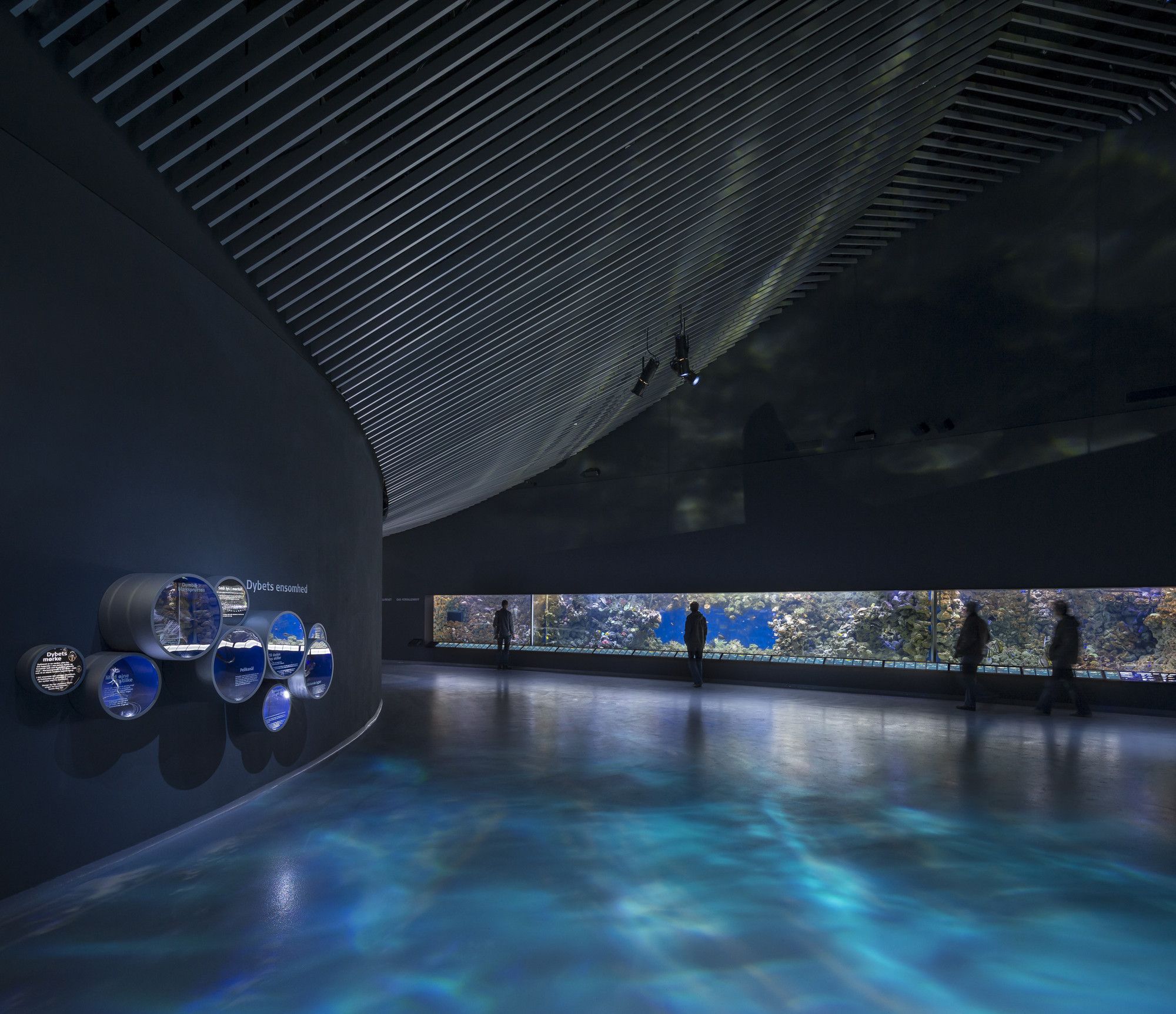

In 1793, “Ménagerie du Jardin des Plantes”, the first modern zoological park, was built in Paris, France, where it continues to be a popular destination to this day. Following the French Revolution, animals belonging to the king and queen were relocated here from the royal menageries. Another notable historical zoo is the London Zoo, founded in 1826 for scientific purposes and opened to the public in 1847. It was located in Regents’ Park, during ongoing developments realized by architect John Nash. In 1853 the London Zoo also opened the first public aquarium, thus expanding the collection to marine wildlife.

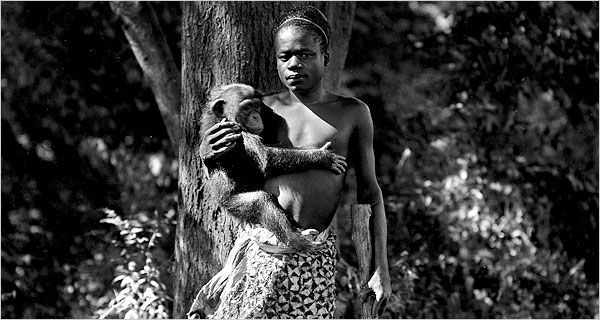

Zoological parks continue to appear throughout Europe – some of the earliest ones include Dublin (Ireland), Hamburg, Berlin, Stuttgart (Germany) or Budapest (Hungary). Unlike contemporary enclosures, the ones existent in earlier stages were minimal. Animals were kept in small spaces, where they were displayed to the public. An even more uncomfortable, painful fact is that earlier zoos even had human enclosures. In 1906, the Bronx Zoo in New York, displayed Ota Benga, a pygmy man, alongside chimpanzees and orangutans, as a “missing link”. The exhibition had few visitors and triggered religious protests.

During the 1970’s, ecology became a major focal point, as a result of extinctions and habitat destruction. The American Zoo Association declared conservation its highest priority, while also making a stop to animal shows. This was part of a re-branding process, as zoos lost popularity. Zoological parks soon became conservation parks or “bio-parks” – a term first used and developed by the National Zoo in Washington DC, in the late 1980s. With decreasing natural habitats and extensive exploitation, not to mention poaching of endangered species for entertainment purposes, the role of such contemporary bio-parks is undeniably important. Still, there still are problems to be solved, even though measures are taken, such as governmental inspections or increasing the space for animals.

One of the major improvements in contemporary zoo design is based on the study of animals’ natural habitats – apart from landscape and architecture knowledge, designers must also have zoological and botanical knowledge. Another positive aspect is the improvement of the exhibition display and the relation between animals and viewers. One of the best examples for contemporary zoo design is the Philadelphia Zoo master plan.

Unlike typical enclosures, with precise limits between visitors and animals, the Philadelphia Zoo master plan proposes a network of trails connecting different habitats and areas. The strategy is based on “animal rotation” and “flex habitat”. Similar features have been implemented in zoos in Atlanta, Louisville, Kentucky, or Cleveland. However, Philadelphia’s is the first one implementing this design strategy at a large scale, making a “very big step”, as designer Jon Coe of FASLA mentioned.

Designing for animals has always seemed to fascinate architects. Take, for instance, Cedric Price, with his bird aviary, Norman Foster‘s elephant house, or, recently, BIG’s cage free zoo that will turn the tables on classical human-animal zoo relations. Why are these illustrious names creating architecture for animals? And, again, there is the question: Is it working? How do animals “appreciate” the design?

Although it is too soon to tell for recent projects, feedback is already available for earlier ones. For instance, the iconic Penguin Pool at the London Zoo, designed by Berthold Lubetkin and Ove Arup, did not seem to satisfy its inhabitants. Apparently, penguins suffered aching joints because of the concrete floor. “The pool is too shallow for them to dive and swim in”, Christ West, of London Zoo, mentioned. “The black-footed penguins housed here have been unable to burrow which is a part of their courting ritual”, he adds. Similar problems appeared in other enclosures, such as Hugh Casson’s brutalist Elephant and Rhino House, also at London Zoo. Although their functionality might be questionable, these projects remain remarkable examples of architecture.

The zoological park has changed considerably over history. With pressing climate or social problems, the zoo as a conservation park seems to be a vital alternative, especially for endangered species. Design strategies are still evolving and continue do to so, along with ongoing research in zoology and animal behavior. Great improvements have been made and many more are yet to come. The least we, as mere visitors, could do is fulfill one of their purposes – learn from animals.

By: Ana Cosma