The Beautiful Intersection of Art and Architecture in Renaissance Painting

Renaissance theoreticians have given architecture a central place among the visual arts, but is there Renaissance art that has an apparent architectural twist? We think of brilliant examples of paintings where religious or historical subjects become an anecdotal pretext for depicting spectacular architecture.

The Renaissance period, which spanned from the 14th to the 17th century, marked a significant cultural and artistic shift in Europe. During this time, artists and architects produced some of the most iconic works of art and architecture that still fascinate and inspire people today.

Renaissance art and architecture were closely intertwined, as artists and architects borrowed from each other’s ideas and techniques. The result was a unique fusion of art and architecture that remains an interesting and important topic to explore. The study of this intersection allows us to better understand the historical and cultural context of the Renaissance, as well as the creative processes that shaped its artistic and architectural achievements.

Architecture and Painting – Two Interwoven Aesthetic Universes

Art’s obsession with architecture can be traced all throughout the history of European art, giving birth to a genre known as architectural painting, where the prime focus lies on urban scenes with majestic buildings. Depth and spatiality fascinate in these works, where the mastery of perspective provides an almost photorealistic spatial impression.

While many of these works depict actual cityscapes, there are plenty of examples where painters reinvent and fantasize about the existing topography by adding imagined architectural repertoire to the historically documented urban environment.

Classical antiquity and the Bible were significant sources of inspiration. We often follow the artists in their quests to reconstruct monumental mythical or historical places such as Babylon with the Tower of Babel or the Lighthouse at Alexandria.

These places are romanticized and imagined as mystical ruins of cities, with beautiful and exotic arcades, colonnades, and entrances. The capriccio became a typical 18th-century genre applied to this poetic blending of real and imaginary architecture.

The veduta was another term coined for a painting of a town or landscape that was essentially topographical in conception and faithful enough to allow the location to be identified (an imaginary but realistic-looking view can be called a veduta ideata).

What are the three main functions of Renaissance painting?

The Ideal City was a programmatic topic in Renaissance art that echoed the humanist vision of the universe as divine, harmonious, and based on mathematical principles. These paintings of cities should represent a utopian architectural model, a calculated ideal civic world not corrupted by trivial life and based on proportion.

Now let’s explore architecture’s three main functions in Renaissance painting:

1- The Depth: Translating Perceptual Space into Visual Space

Architecture is the making of space – a catchword known by everyone who is in any way engaged with the construction industry. The difference between architecture and painting is rooted in how we experience space. Architecture offers an immediate interaction with the physical, three-dimensional space. This perceptual phenomenon is inevitably translated as flatness in painting and arranged with the help of linear perspective as an imitation of depth.

For the sake of mimesis, painting is fascinated by the physical space and is always trying to transcend the boundaries of its medium, the canvass, to capture what is beyond its imminent flatness. The painting is expected to achieve this with the help of architecture as a pivotal structural element of the composition.

Perspective operates through exterior or interior architecture, granting privilege to only point of view by introducing parallel lines that converge in a vanishing point; this is how we perceive spatiality in painting. Perceptual space turns into visual space – a transformation of brilliance.

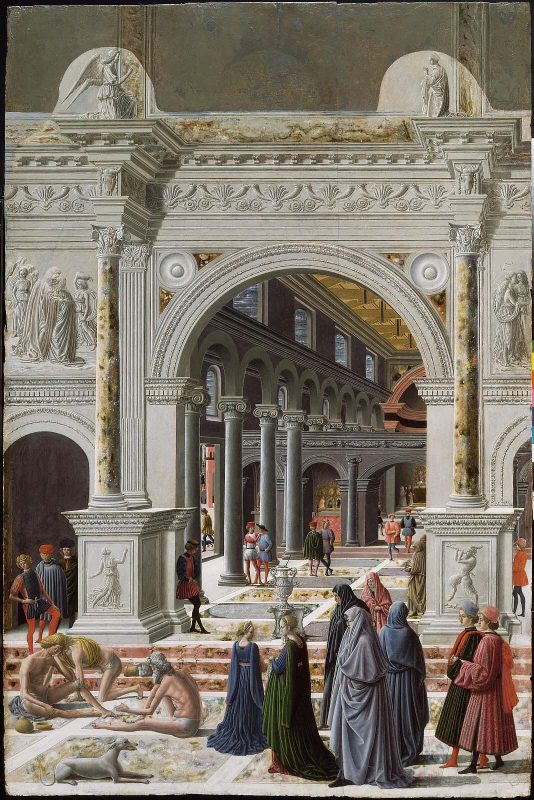

As in the beautiful painting by Domenico Becafummi, The Story of Papirius, architecture is an active element in constructing the painting’s visual spatiality through perspective.

We can literally imagine ourselves stepping into the landscape unfolding on the right-hand side, walking toward Senate monuments, or climbing the stairs underneath the arches of the Roman Senate to the left. This also frames the main anecdotal event of the narrative: the pleading of the Roman matrons for the legalization of polyandry after Papirius’ lie.

The painting has attempted to give us a perceptive reality of the iconic architecture of the ancient Roman setting where the story takes place, appearing as a visual space we could imagine exploring physically. Far away in the distance, we observe the crumbling ruins on the Palatine hill bathed in the horizon’s mild pink air, with ancient Roman temples, a ruined aqueduct, Emperor Hadrian’s mausoleum, and parts of the Colosseum getting progressively small and distant.

Typically, an inevitable blending of anSenateand contemporary structures creates an architectural anachronism. The Senate resembles, in fact, a Renaissance loggia, and the representation of the Roman monuments reveals topographical and chronological distortions.

2- The Frame – Creating Conceptual Spaces

The conceptual space in architecture is the mental plan developed and stored in our memory regarding the building’s structure, model, and features. Our mental eye creates a preliminary blueprint of the building that is rational and analytical concerning the construction’s anatomy and specifications. The exquisite colonnades, arcades, and facades gracing many Renaissance artworks function as conceptualizations regarding the painting’s narrative structure. They visually constitute the narrative space of the picture and signify the ontological border between physical (real) and narrative (fictional) space.

The painter translates this physical border into a concept by applying architectural elements on the panel’s sides or within the picture. The frame designates the painter’s selection of the depicted protagonists, events, or details, allowing the narrative to manifest itself in completeness; it sets beginnings and ends, adds secessions and rhythm to the picture, and creates the illusion of an open window (aperta finestra) before the viewer, through which they are gazing at an aesthetic universe that is coherent, harmonious and centered.

Thus we should not consider architecture an added quality with very decorative purposes but a conscious approach to image-making and structuring the visual narrative. By including sculptural or architectural elements within the frame, artists could enhance the three-dimensional qualities of their works.

Very often, the rich frame of painted architecture served as a conceptual entity to give the narrative balance, symmetry, and completeness. By articulating space through architecture, painters managed to create narrative multi-dimensionality in the form of stories within stories or by adding layers to a particular story.

Architecture is one handy framing device used as a continuous narrative for depicted events, synchronically illustrating multiple scenes taking place at different moments within a single frame. Compositions were generally arranged around framing devices such as arches, arcades, or doorways and contained marvelous architectural structures around which the events were organized.

Architecture is a border between these multiple scenes, like in the above painting, The Story of Papirius. Three different episodes – Papirius’ lie, the procession of the Roman matrons, and ThSenaten’s pleading to the Senate are depicted together on the canvass even though they do not happen simultaneously. The architecture establishes frames within the visual structure and differentiates these multiple events.

In the diptych by the architect and painter Fra Carnevale from Urbino – a student of Filippo Lippi and later a Carmelite monk, The Birth of the Virgin (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York) and Presentation of the Virgin in the Temple (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston), we see how architectural frames to segment the space into different events to form narrative and temporal layers.

The story’s focal point is the bathing of the baby Maria with several maidens depicted in the middle ground. In the background, under the arcades, we see St Anna positioned in a bed and accompanied by servants. In the painting’s foreground, a group of women with prayer beads and well-wishers ceremoniously greet each other, walking or riding on the left-hand side.

The reliefs serve decorative purposes and suggest the baby’s sex via a portrayal of an ancient scene with a nereid and a centaur. Demarcation points between inside and outside particular architectural structures also serve narrative purposes. It is interesting to observe how the interior and exterior spaces of the specific building blend together –we still see inside a room and a building through an unrealistically frontal open area – a method that explicitly shows architecture’s role as a framing device.

In the second painting, Presentation of the Virgin in the Temple, the façade depicts events in the Virgin’s life—the Annunciation and the Visitation. The central scene revolves around the Virgin’s procession and passing by a group of beggars before entering the temple’s beautiful arcade.

Being an architect, Fra Carnevale couldn’t have resisted portraying the intricate friezes and rows of Ionic columns that frame the inside of the church’s interior. There, creating architectural perspective, the master adds layers to the scene with stairs dividing the foreground space from the interior part, viewed through a large, classical arch.

3- The Scene – Translating Behavioral Space into Narrative Space

The architectural décor in Renaissance painting is a crucial component of the scene’s visual orchestration. One of architecture’s grand masteries is the decisive shaping of behavioral space – the space we can navigate through and utilize – a performative space that constitutes a potentially dramatic realm for action.

Events indeed take place, and transforming a behavioral space into a space for the narrative spectacle to manifest itself is one of architecture’s roles in art. The area becomes part of the action; it is the primary substance of the scene, and being transformed into a narrative space, it is meant to be able to tell the story by its means.

Architecture is a richly informative cultural artifact with infinite narrative qualities. Masses, structures, and decorations speak for themselves, enclosing and defining foregrounded spaces where something happens, with spatial articulations essential for the depicted event.

This is what we call an architectural setting, where behind the apparent objectivity of painted buildings and facades, the architecture is a crucial element in processing sacred or political messages or designating the historical and geographical context of the scene. The brain interprets a figure seen in the context of its enclosing space as a form against the scenery, and this is a symbiosis of fundamental significance.

The Sermon of Saint Stephen by the Viennese Vittore Carpaccio at the Louvre Museum in Paris takes place in Jerusalem. To indicate the location, the painter used scenic architecture.

Surrounded by the walls of Solomon’s Temple, St. Stephen is situated on a ruined ancient pedestal that had to symbolize Christianity’s victory over paganism. The urban setting – executed carefully and spectacularly unfolding around the protagonist, is by some historians identified as the 16 century Damascus with its mixture of ancient Greco-Roman and Islamic architecture.

Examples of paintings that depict the Ideal City and how the architecture in those paintings contributes to the overall meaning of the work

The theme of the Ideal City has been explored in several artworks throughout history. Some of the notable examples include:

- “Ideal City” by Fra Carnevale, “The Garden of Earthly Delights” by Hieronymus Bosch, and “The City of the Sun” by Tommaso Campanella. These works depict a utopian vision of human society, where architecture is characterized by order, balance, and harmony.

- In “Ideal City,” Fra Carnevale presents an imaginary city with symmetrical buildings, domed temples, and a central plaza. The painting reflects the values of the Renaissance era, emphasizing the pursuit of perfection and the balance between man and nature.

- On the other hand, Hieronymus Bosch’s “The Garden of Earthly Delights” features a highly stylized and fantastical version of a Renaissance city with elaborate, multistoried buildings and winding streets. The architecture in the painting emphasizes the excesses and decadence of human society, leading to the downfall of civilization.

- “The City of the Sun” by Tommaso Campanella is a utopian treatise that describes an imaginary city based on principles of reason, equality, and justice. The architecture in the book reflects these ideals, featuring buildings and public spaces designed for maximum efficiency, comfort, and communal living. The City of the Sun represents a vision of a perfect society in which humans live in harmony with one another and with nature.

Overall, the architecture in paintings depicting the Ideal City serves to reinforce the utopian vision being presented. These works often feature highly stylized and fantastical versions of architecture, emphasizing symmetry, balance, and order. The Ideal City represents a vision of a perfect society in which humans live in harmony with one another and with nature, and the architecture in these paintings reinforces this ideal.