When you hear the term “Black Aesthetics” perhaps the first thing that comes to your mind is the chic, luxurious black interiors, but there is more to it than that—it can refer to approaching architecture that unfolds the black people’s urban struggle, or in a more positive manner, celebrates the black people’s identity.

Maybe including communal space in every context is one way to reduce racism and inequality—but is it enough? These black aesthetics are not well celebrated; not in architecture schools classrooms, not in architectural firms, and not even in the real estate industry. To state some facts, the total number of black architecture students has remained at or near 5% for nearly a decade, and just 2% of the 116,242 licensed architects in the United States and its territories are black.

One of the 5%, Demar Matthews, sat down to find out what his thesis would explore, and he could not escape the fact that there is no truly black aesthetics in built architecture. One of the -frankly- inspiring architecture school incidents Demar Matthews mentioned is the following.

Recently I experienced a changing incident with a professor who was reviewing my work alongside that of my classmates after a pin-up. He was excited about all the work and decided to issue individual comparisons to architects in the field.

He went down the line commenting to my [white] classmates: “You could be like Eisenman,” “You could be like Frank Gehry,” etc. When he got to me, he failed to think of an architect who looked like me, and instead said that I could “be like Obama,” because there aren’t many black architects.

Through his thesis, Demar wanted to explore the Black Aesthetics of architecture in America, and to do so, he designed a 700-foot Accessory Dwelling Unit (ADU) in Los Angeles‘ Watts neighborhood. He dubbed his project “Unearthing the Black Aesthetic” and it called for architects to participate in designing an artists’ residence.

Where was the architecture that spoke to my identity as a Black person? This is the driving question in my thesis which seeks to develop and identify a Black aesthetic in architecture.

How “Black Aesthetics” Celebrate Black Culture’s Architectural Identity?

“Unearthing the Black Aesthetic” was initiated to celebrate black culture and -more than that- open a window for this culture to get recognized for its true identity and not the stereotyped one. Demar’s project not only focuses on the built and tangible part of an urban context but also the attributes of music, art, fashion, and even language.

-

Hairstyles

Demar studied the geometric patterns of popular African American hairstyles such as box braids and curls and used these forms to create patterns and architectural motifs that could relate to the culture and create a black aesthetic.

-

Slang

He also analyzed language and extracted the words most used in African American communities, such as “woke” meaning ‘well-informed’ or ‘aware’, especially in a political or cultural sense, and “turnt,” and “lit” meaning excited or energized. Demar then associated this slang with architectural designs that best evoked their meaning. For example, the slang “woke” was paired with the National Museum of African American History and Culture, which was designed by high-profile architectural firms that included Black designers like David Adjaye and Phil Freelon.

-

Dance

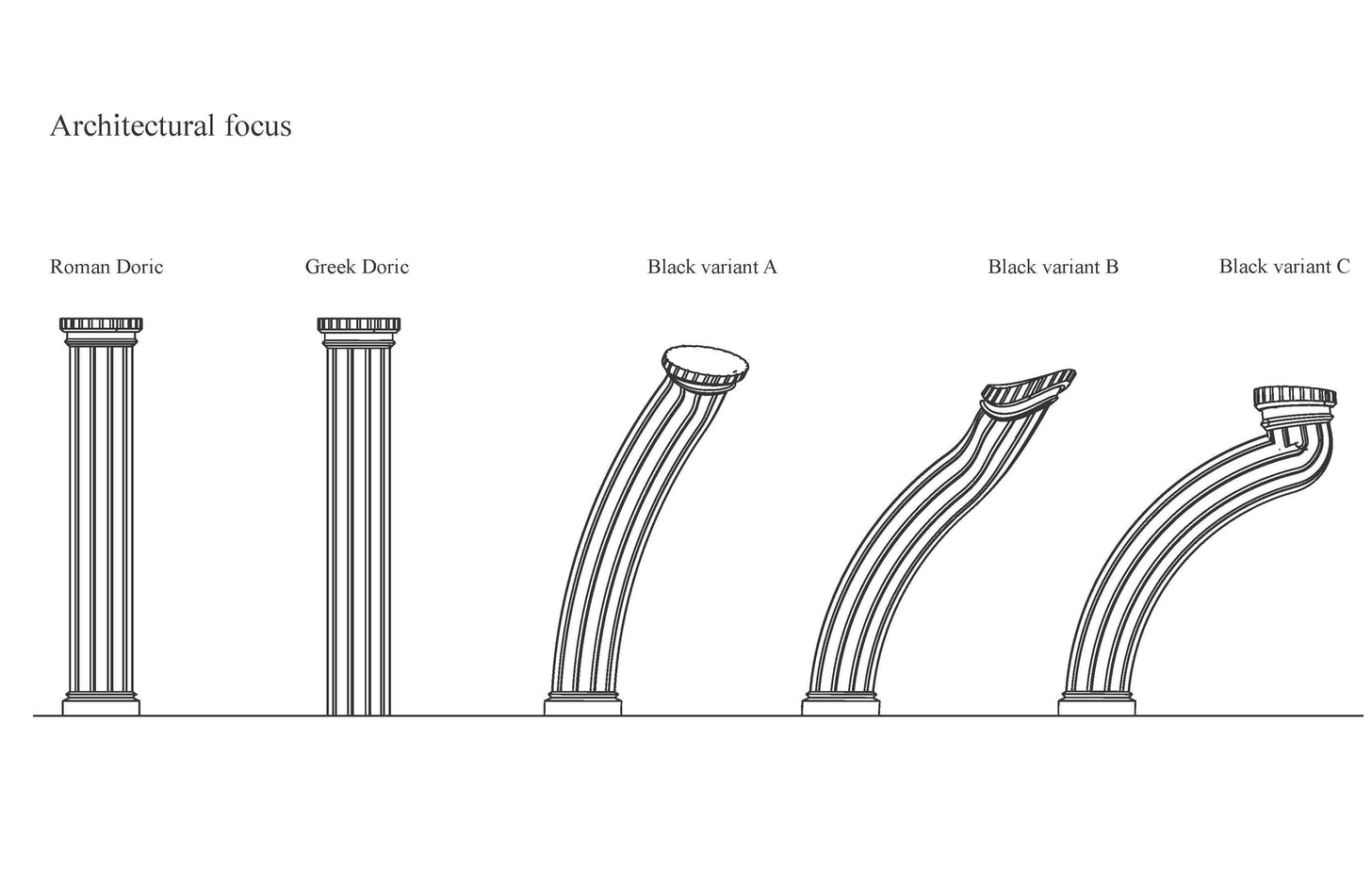

Demar Matthews was inspired by artist Earnie Barnes’ painting titled “Sugar Shack” and wanted to highlight the unique body language of black people. In the painting, the characters “have eccentric and fluid motions about them that make their movements seem elastic”. Besides this, Demar thought of the popular dances designed by African Americans and translated these moves and elasticity into his own interpretation of popular architectural elements.

The final result of Unearthing the Black Aesthetic took form in the “R Cloud House”; a building that takes the shape of a crown-shaped structure with a pointed roof and a facade covered with the studied patterns and motifs. The diagonal form of R Cloud House is inspired by shotgun houses; narrow rectangular domestic residencies that were the most popular in the Southern United Stated through the 1920s.

The Architecture of Unearthing the Black Aesthetic

When asked about how his project relates to architecture, Demar explained how each culture has its own architectural style based on the values, goals, morals, and customs rooted in the communities of this culture. When these cultures relocated, they rebuilt versions of their hometowns to maintain a strong aspect of their identity; their environment and urban context.

However, this is not the case with African Americans; as until 1968, Black people in Los Angeles had no right to own property, and in many other cities, the process was really difficult to the level of being practically impossible.

“…while others began the race of acquiring land in 1942, building homes and communities in their image, we were held back behind the starting line. The Black community started running 476 years after the race began.”

—Explained Demar in an interview with Archinect

This inequality surely affected the black culture, and this is what drove Demar to start developing a Black Aesthetic in architecture—the realization that there is no architecture “that spoke to his identity as a black person”.

What is Next for Black Aesthetic?

Now 29 and a Masters of Architecture graduate of Woodbury University, Demar is working hard to get his designs to reality. Luckily, before he graduated, a professor connected him with a Watts community activist. Janine Watkins owns a property in the neighborhood and she uses it to host artist residencies.

Fascinated by Demar’s thesis, she invited him to realize his building on her property and, more than that, turn the main house and garage into a mixed-use space for other community purposes. Moreover, Demar started his own architectural studio, OffTop Design, to go further through this path of Unearthing Black Aesthetic. His goal is to design nine buildings, including public buildings such as a community center.

Community activist Janine Watkins, left, and architectural designer Demar Matthews at Watkins’ property in Watts – Photography by Monica Orozco

Demar used his architectural design skills to tell a story about his identity and the place he came from—a story that is already on its way to change minds and communities, and you can, too. Arch2O opened a window for you to use your architectural design and architectural drawing skills to tell a story of your own.

Arch2O One Drawing Challenge

Arch2O created an architectural drawing challenge, the registration started just last week, the 10th of October, and will remain open till the 15th of November. Architects consider drawings as their official language; it is how they connect, communicate, and -most importantly- tell stories.

Ranging from abstract to highly detailed, and from strictly engineered to highly illustrated, architectural drawings give different senses of their context. The Arch2O Drawing Challenge calls for architectural drawings that convey the notion of their location and culture and tell stories of how people connect with these buildings.

To be part of Arch2O’s challenge, submit a single drawing that tells a significant story about architecture: how the built environment interacts with its context and inhabitants. The submitted drawing can be located anywhere in the world, be at any scale, and can represent an imagined architectural proposal or an existing work of architecture. The drawing should be categorized under the following: plan, section, elevation, perspective (1 or 2 points), parallel projection (axonometric, isometric, etc…), sketch, detail, or abstract.