Le Corbusier has designed some “grand projects”, but is the United Nations Headquarters one of them? There is a lot we do not know about the pioneering architect.

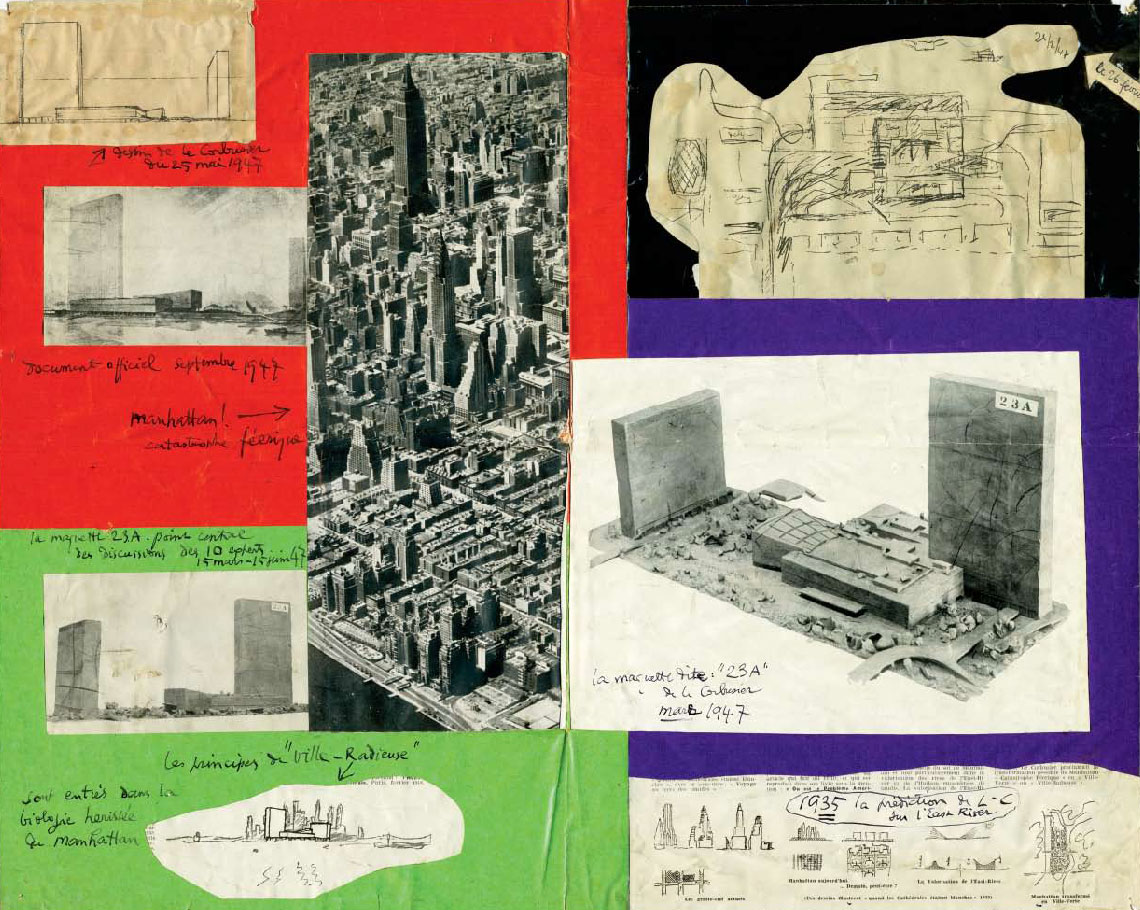

Today -the 24th of October- is United Nations Day. Two years after the intergovernmental peace-seeking organization was founded, it started planning for constructing an international headquarters and settled on a land plot looking over the banks of the East River in New York City; a city that was geographically accessible for all members of the UN to come together.

That was back in 1945, World War II has just ended and everyone is tiptoeing—as part of their peacekeeping agenda, the UN invited some of the world’s prominent architects to collaborate on this project instead of creating a competitive atmosphere—their assignment was to design a Headquarters that would be “a symbol of the bright, peaceful future ahead that did not dwell upon the past.”

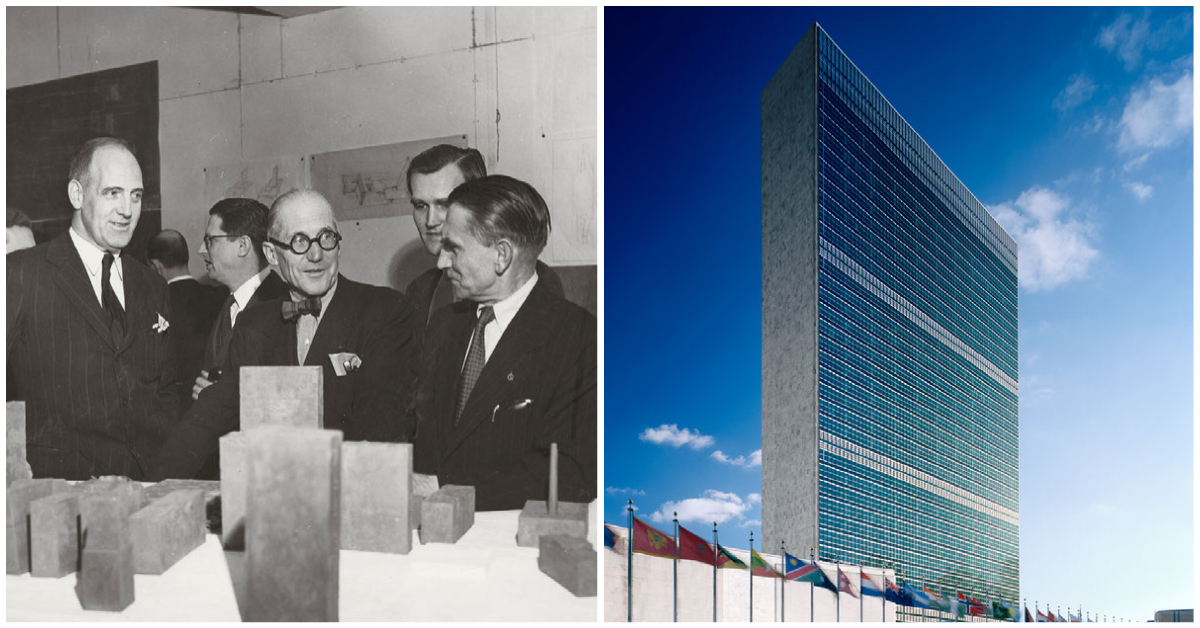

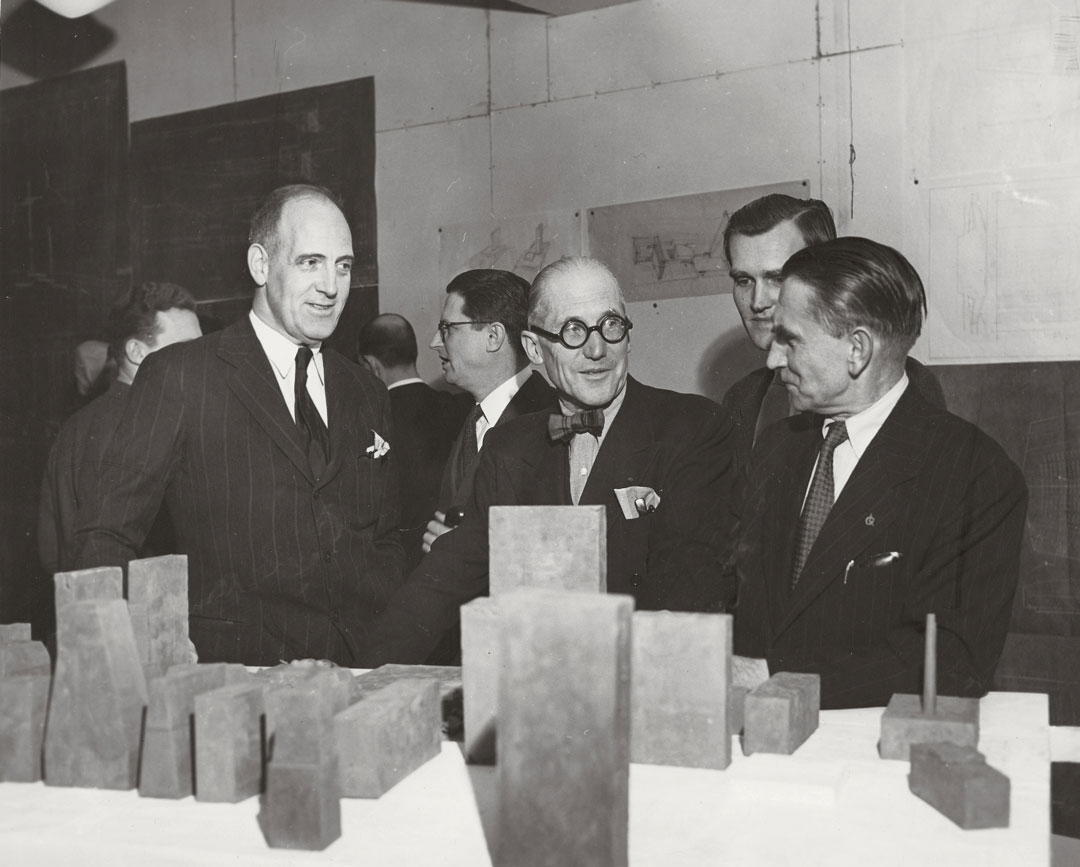

Led by the American architect Wallace K. Harrison, the international team to design the UN Headquarters included Le Corbusier from France, Oscar Niemeyer from Brazil, Howard Robertson from the UK, and several other iconic names in the world of architecture.

A Little Backstory…

By the end of the 1920s, the Swiss-French architect Le Corbusier was only determined to work on major commissions, or what he called “Les Grands Projets”. One of these grand projects was his proposal for the competition to design the League of Nations Headquarters in Geneva.

Le Corbusier, standing behind a display of models for the UN complex with Wallace K. Harrison (left) and Vladimir Bodiansky (right), 1947. Picture credit: Courtesy Fondation Le Corbusier, Paris

Le Corbusier wanted to achieve his “Five Points of a New Architecture” on this project, however, luck was not on his side—the pioneering architect lost the competition.

“…his loss of the competition and the ensuing controversy was the source of tremendous personal bitterness, […] though it also generated worldwide celebrity for the ambitious architect.”

—Jean Louis Cohen, Tim Benton

Flash forward to 1947, Le Corbusier was chosen to be part of the Manhattan UN Headquarters design committee, and he chose to “put forward his own plans quite forcefully.”

Why Does Le Corbusier Claim the UN HQ is His Own Work?

The architects were asked to develop several proposals for the HQ of the United Nations, both collectively and individually. However, at the beginning of their collective meetings, it is believed that Le Corbusier was trying to impose his thoughts on the committee.

Le Corbusier encouraged Oscar Niemeyer to abandon his own design endeavors to join forces with Corbusier; however, Harrison strongly encouraged Niemeyer to explore his own ambitions throughout this process.

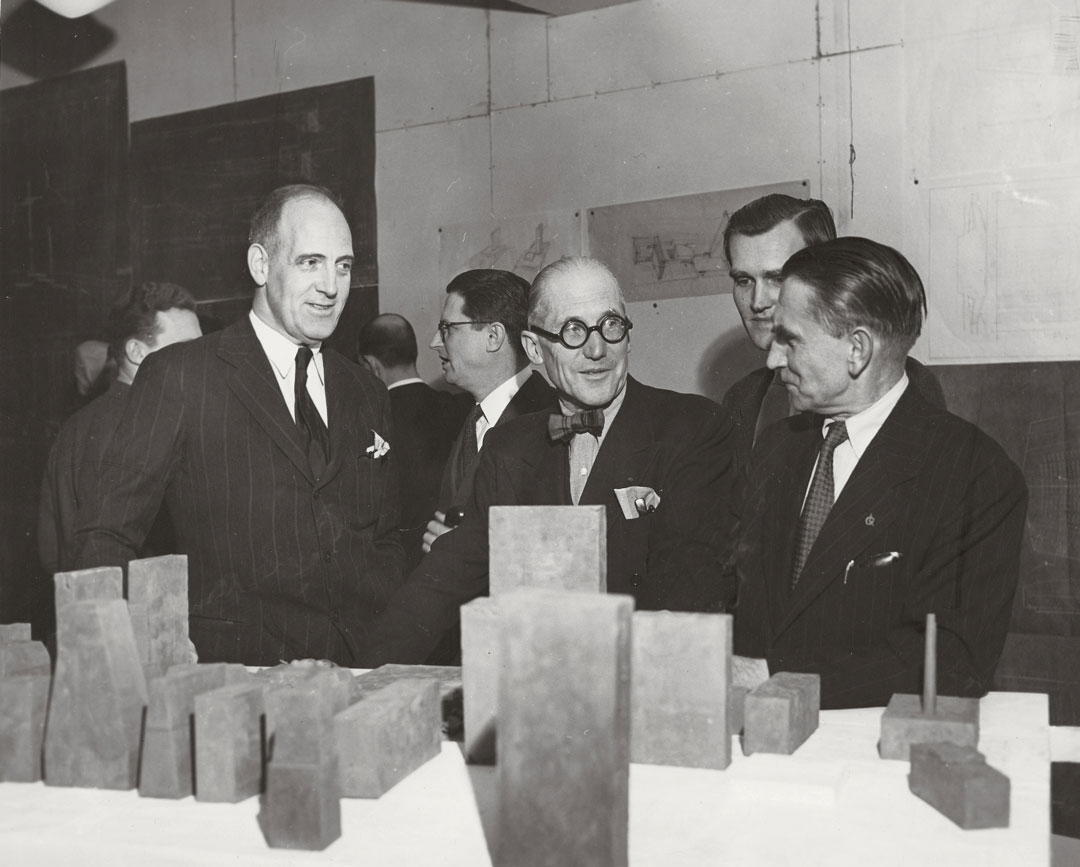

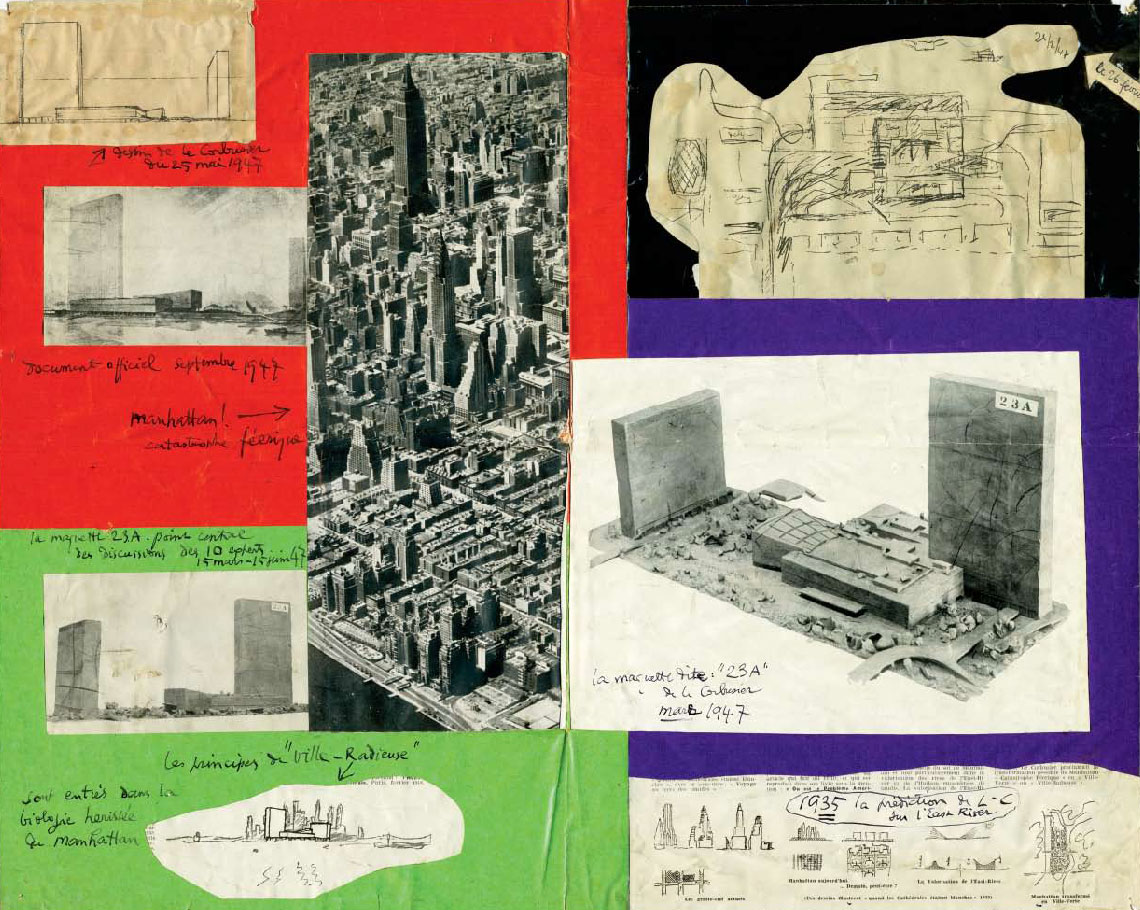

Above. A 1947 collage of plans, models, and drawings for Project 23A, with an aerial photograph of Manhattan encompassing the project’s site. From Le Corbusier Le Grand

At the end of the process, the committee had come with fifty design proposals for the United Nations Headquarters. Ironically, the two determining schemes for the project were between Oscar Niemeyer’s scheme 32 and Le Corbusier’s scheme 23.

In the end, Niemeyer’s strategy that proposed the separation of the Secretariat Building and the General Assembly into two large towers as a way in which to create a large civic plaza across the base of the site was chosen over Le Corbusier’s centralized Secretariat Building and General Assembly that were vying for a sense of hierarchy on the site.

Surprisingly, even though the council had chosen Niemeyer’s strategy as the winning scheme, Le Corbusier pressed his design for the General Assembly on Niemeyer as a better location and compositional design than his proposed two towers.

Although the change would, in effect, destroy the large civic center that Niemeyer had envisioned, Niemeyer allowed the repositioning of the assembly stating: “I felt he would like to do his project, and he was the master. I do not regret my decision.”

Today, the United Nations sits as it was planned in 1947 as a collaboration of Oscar Niemeyer’s 39 stories, International Style tower, and Le Corbusier’s slanted general assembly building while still maintaining some semblance to Niemeyer’s civic plaza with a large park overlooking the East River.

Le Corbusier’s humiliating loss of the League of Nations competition twenty years earlier repeated itself in 1946–47 in New York, where he spent many months trying to impose his views on the committee responsible for designing the United Nations headquarters. Although he was not allowed to take charge of the project, he never ceased to assert that the finished building was based on the model he claimed was his design.

—Jean Louis Cohen, Tim Benton

Officially, the building’s design is credited to the committee -which included Le Corbusier- though many say that the completed complex more closely resembled the designs submitted by the Brazilian architect Oscar Niemeyer.

Given that Niemeyer was originally Le Corbusier’s junior -both age-wise and in terms of professional hierarchy-, Le Corbusier did not accept the fact that the United Nations Headquarters in Manhattan was not completely designed by him.

“Niemeyer, one of ten architectural delegates working on the project, had been Le Corbusier’s associate on the Ministry of Education building in Rio de Janeiro ten years earlier,”

Further Allegations

There are more claims regarding the matter, including that Le Corbusier has done more than forcefully imposing his thoughts and proposals on the committee—a signed affidavit from Max Abramovitz, the American architect who helped oversee the committee, states that, after the final plan for the HQ had been settled on, “I saw Mr. Corbusier [sic] take off the wall the sketch of the plan referred to above, redraw it in his own hand and style, redate it, initial it, and put it back on the wall.”

“to the end of his life, he remained bitterly insistent that the building was based on his design.”

—Jean Louis Cohen, Tim Benton

y

A Tour Inside The United Nations Headquarters

In its current state, the United Nations has evolved into an organization of 192 member states. Even though the site adjacent to the East River has been the permanent residence of the United Nations for over fifty years, there are still attempts from other countries, foreign dignitaries, and even Manhattan residents to persuade the UN to move out of the United States. Until then, Niemeyer and Corbusier’s design for the United Nations will continue to give promise to a brighter tomorrow that does not dwell on the past, both politically and architecturally.