Palace of Justice

In 2006, an international competition was held for the Palace of Justice, in Córdoba, Spain. Mecanoo won, but due to economic instability the project was delayed – but now things have started to move again, and the project is due for completion in 2017.

For centuries, the moors occupied of the Iberian peninsula, leaving a lasting impression on its most southern territories, particularly on Andalucia. Thus, Córdoba is a city of deep moorish and islamic traditions – and it is in this genealogy that the Palace of Justice attempts to integrate itself.

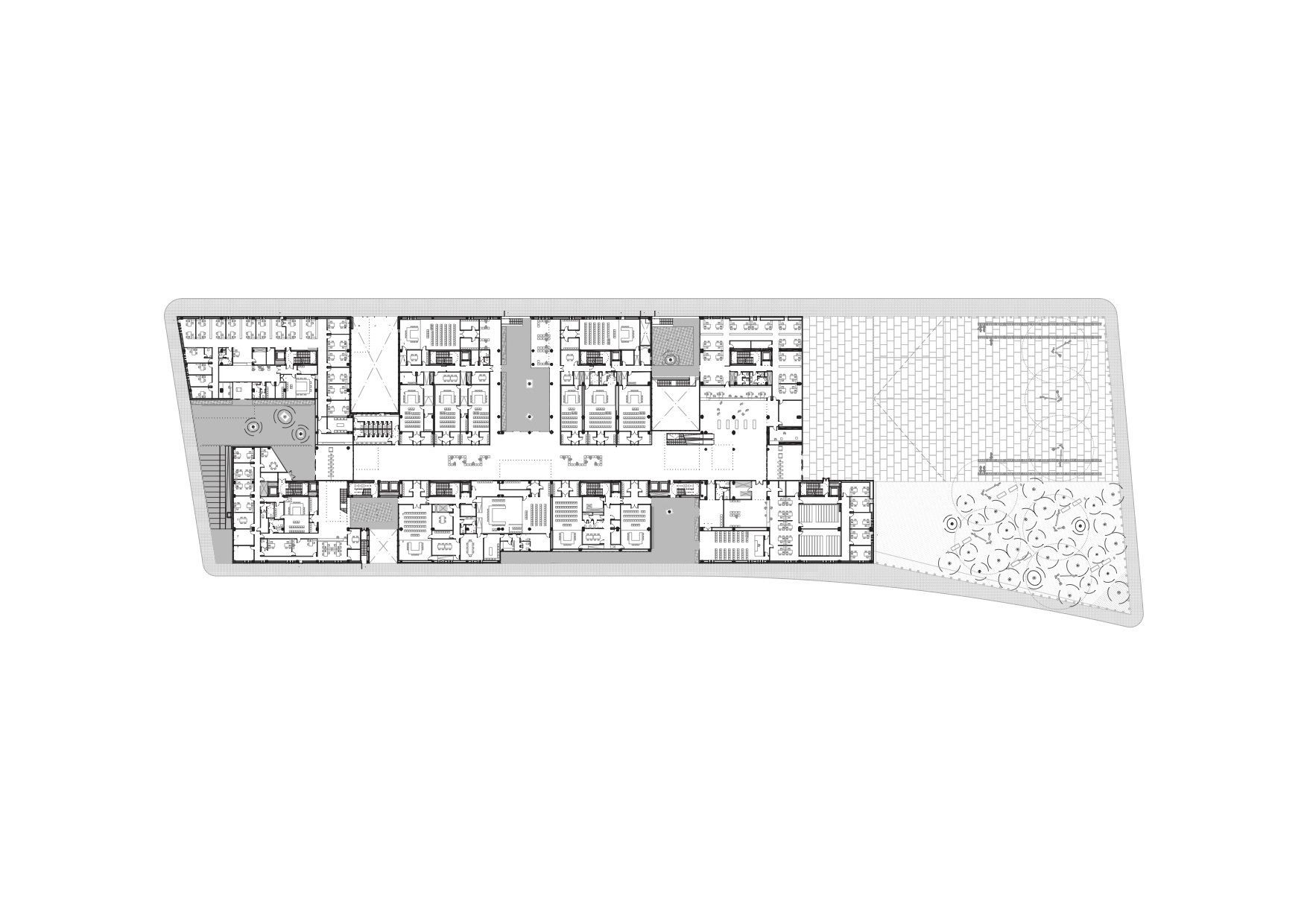

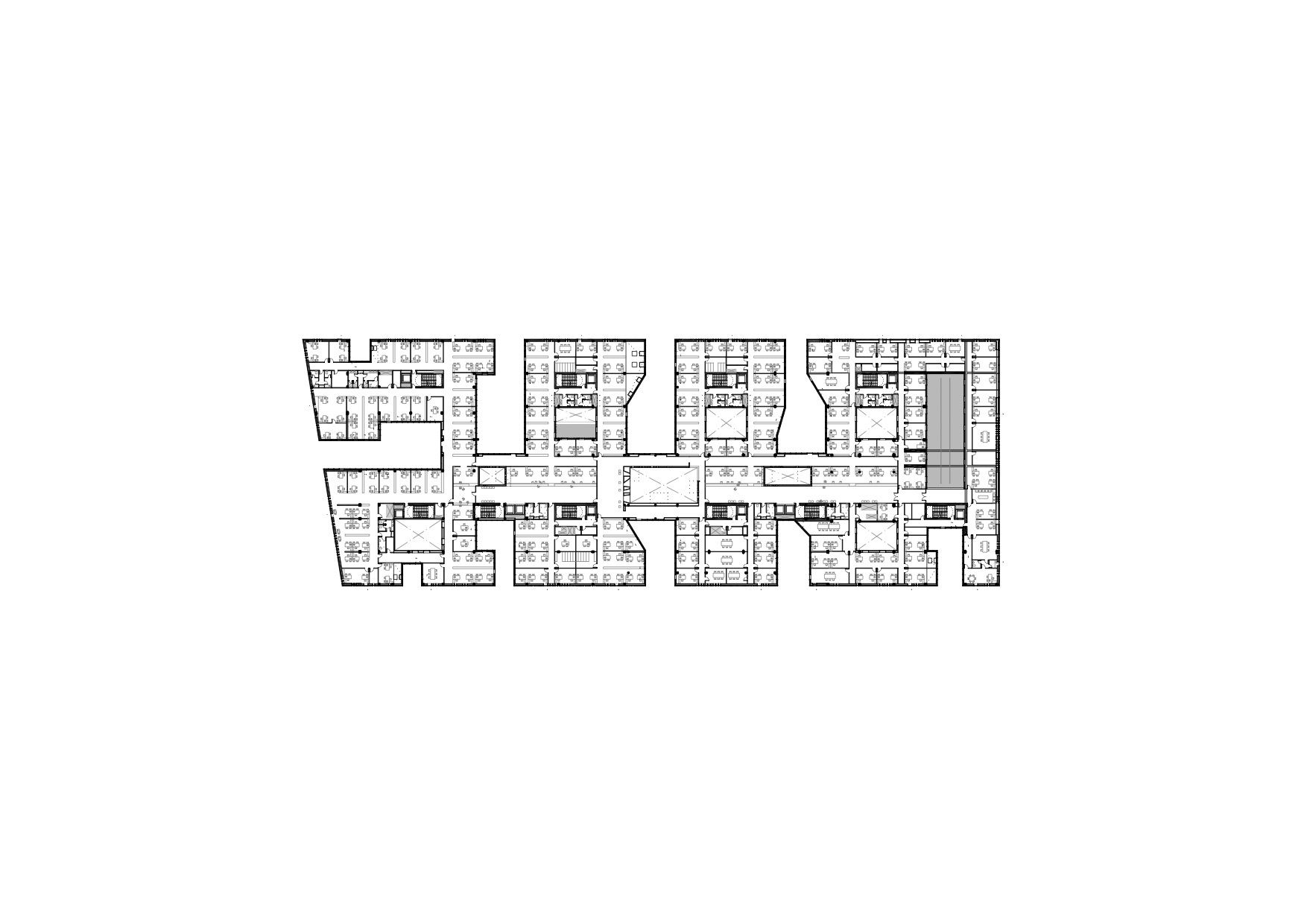

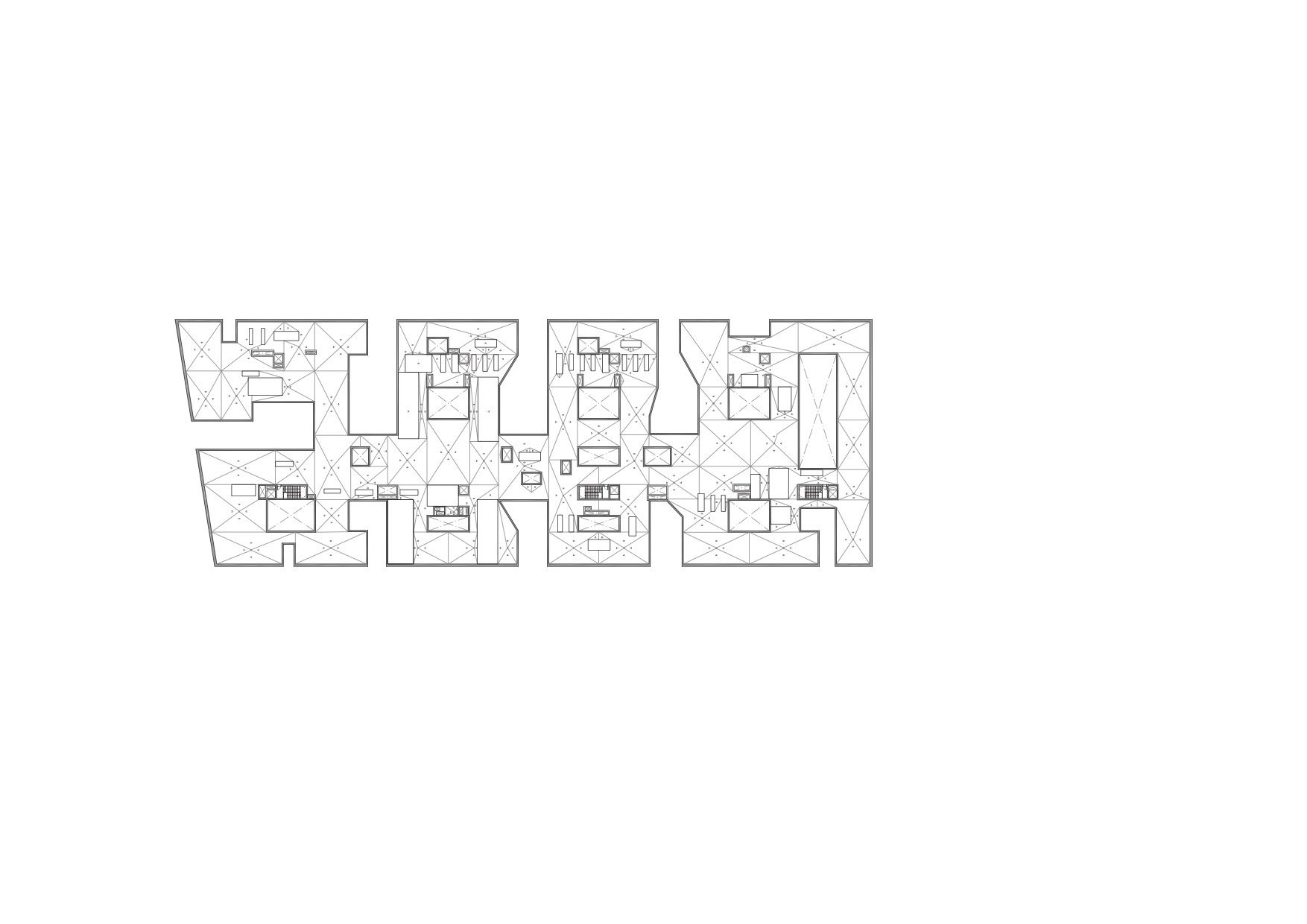

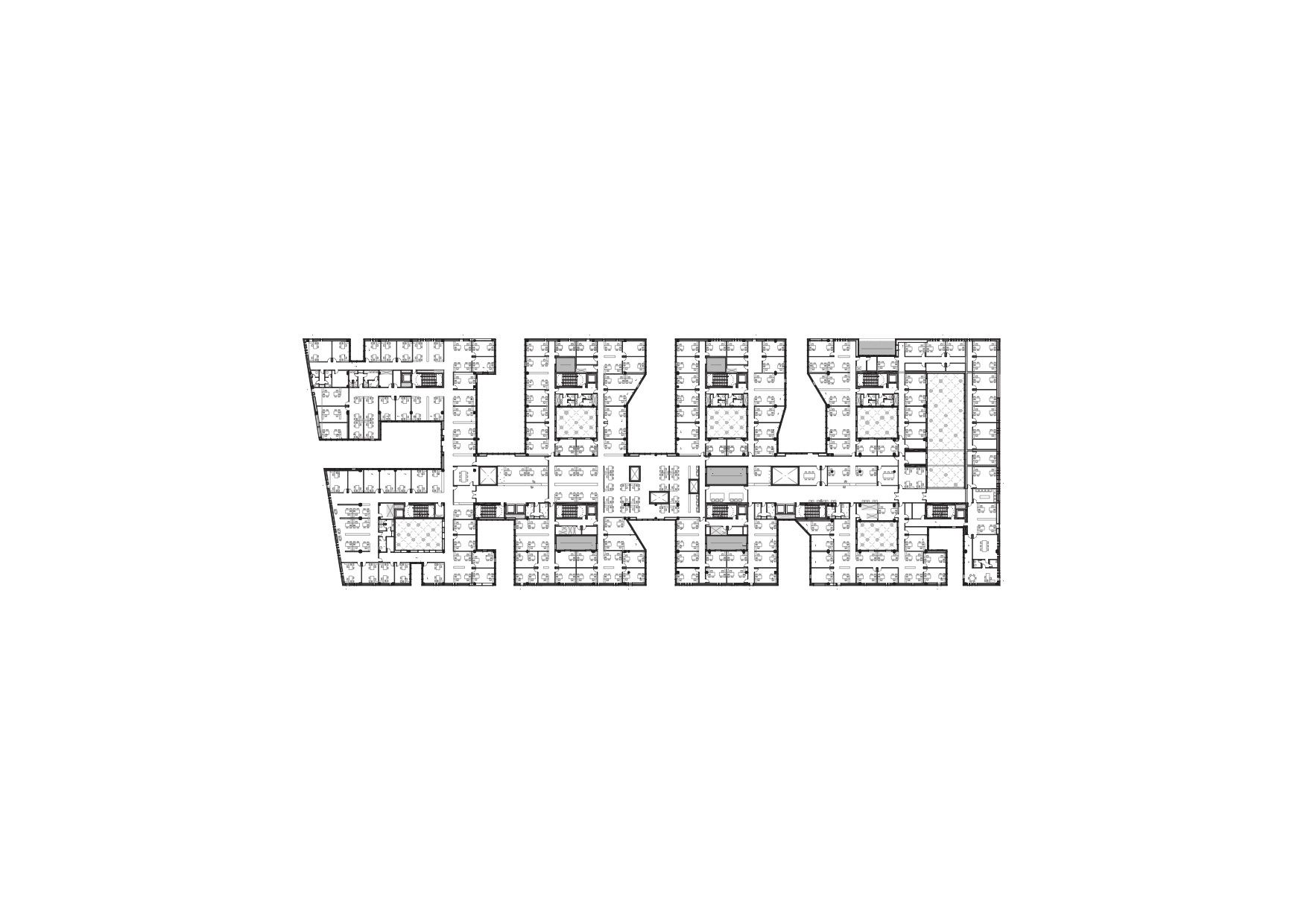

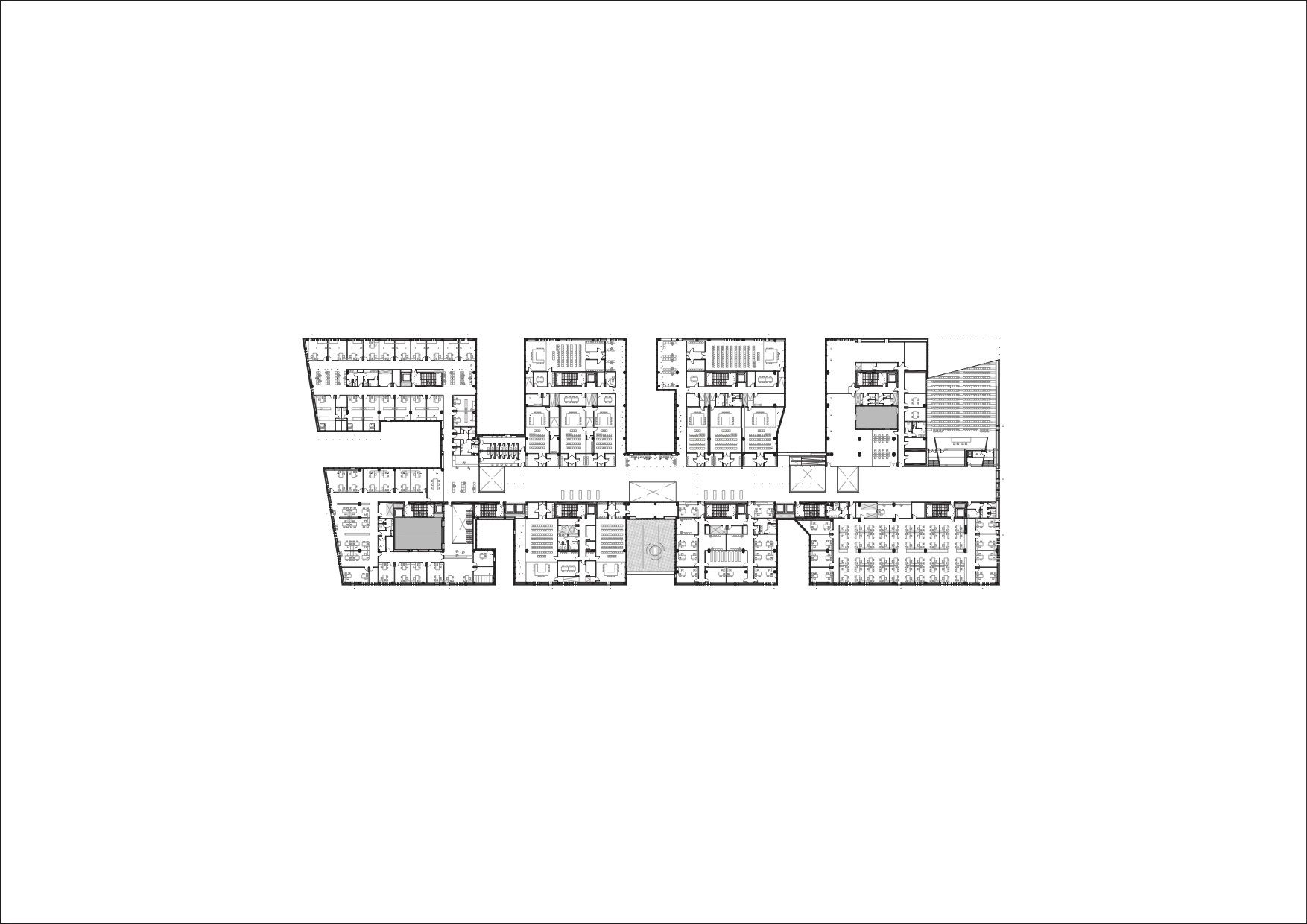

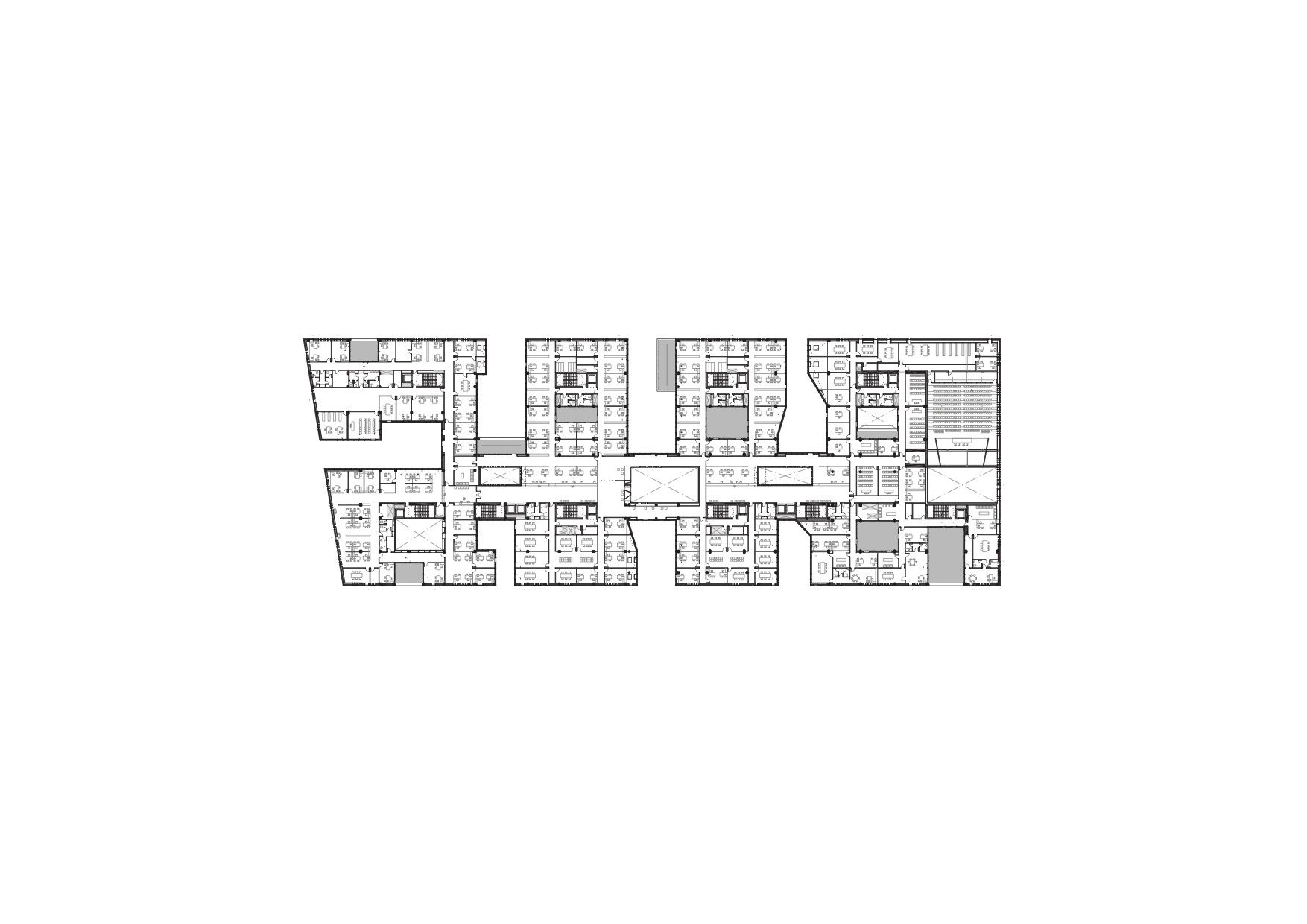

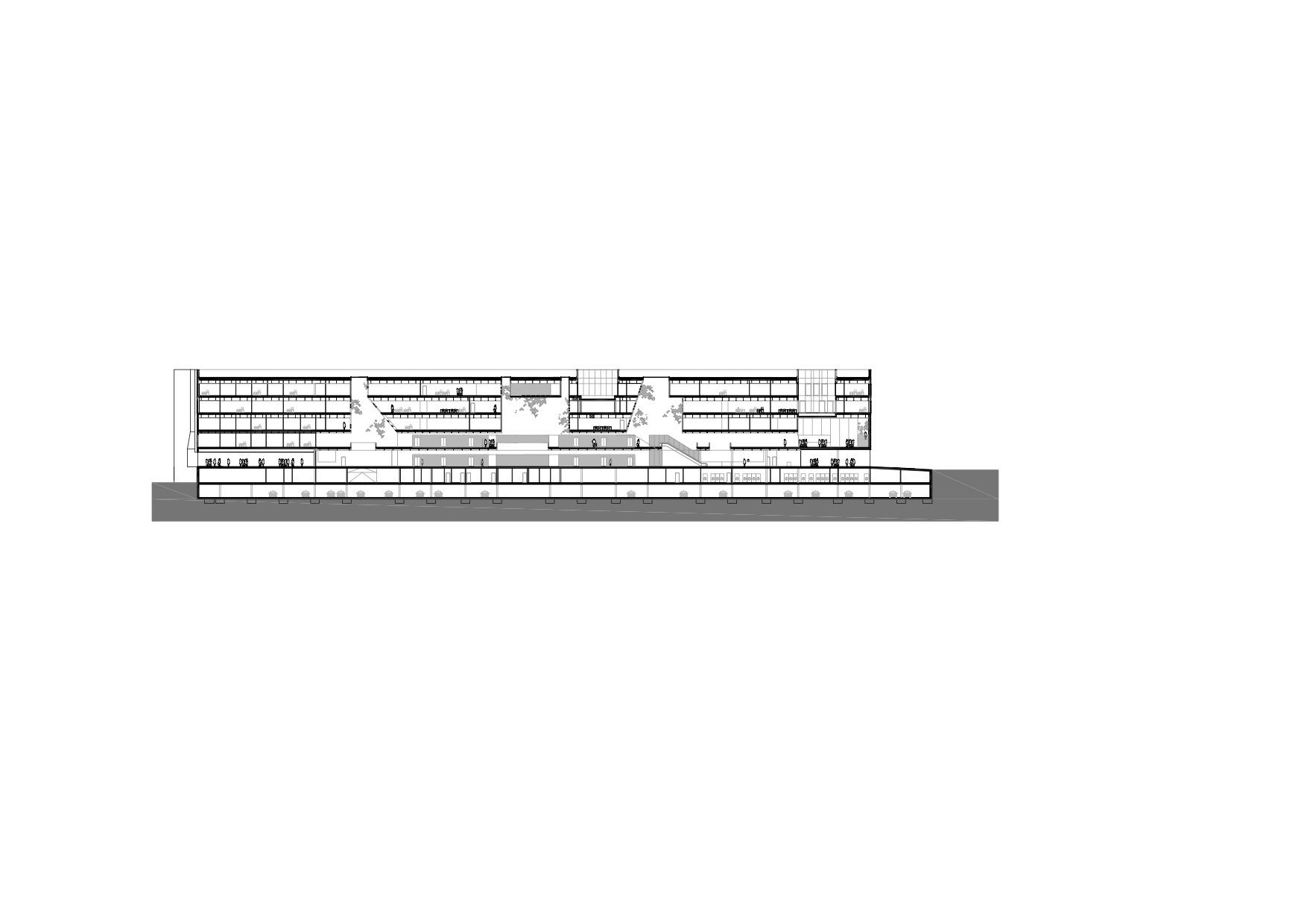

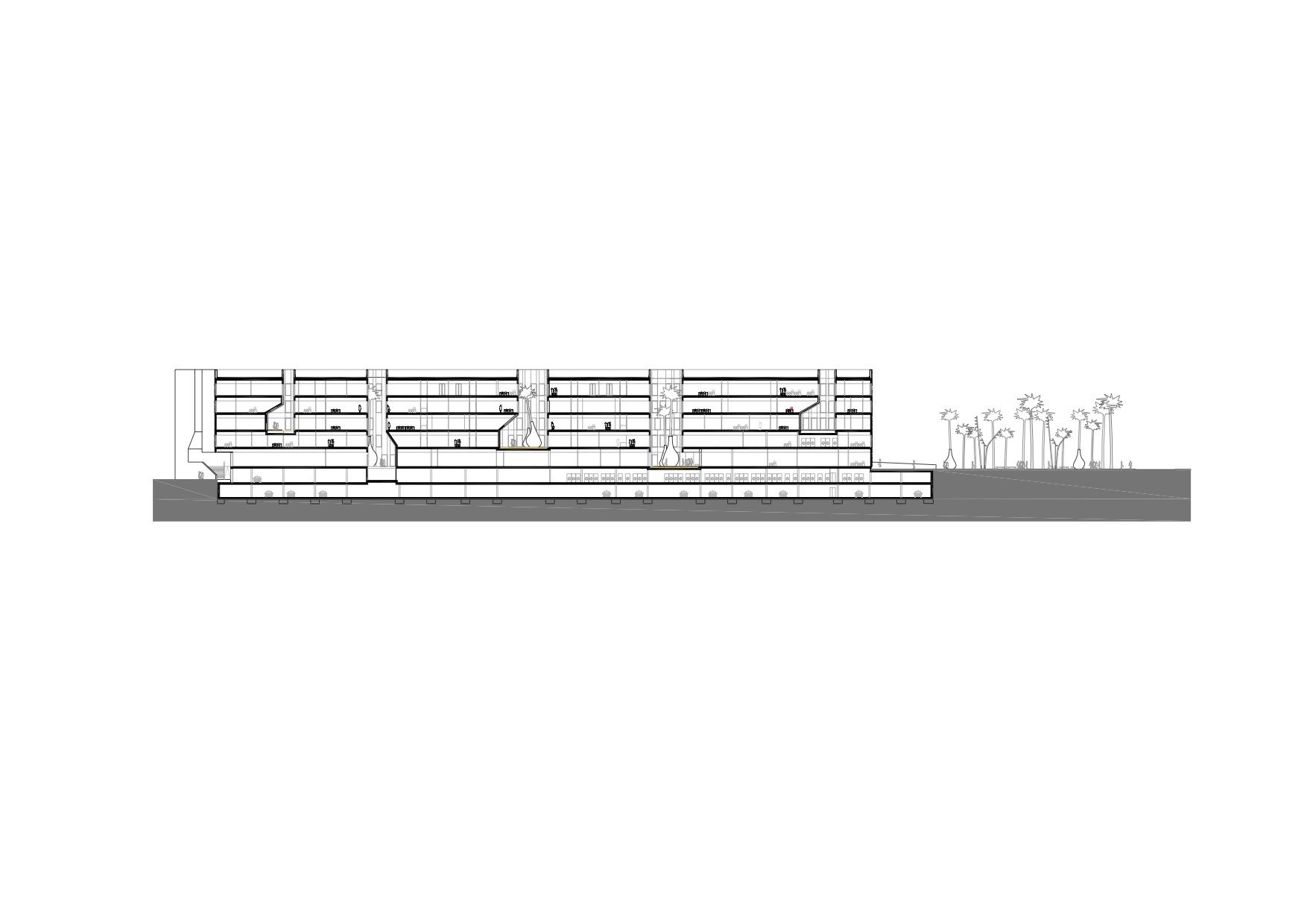

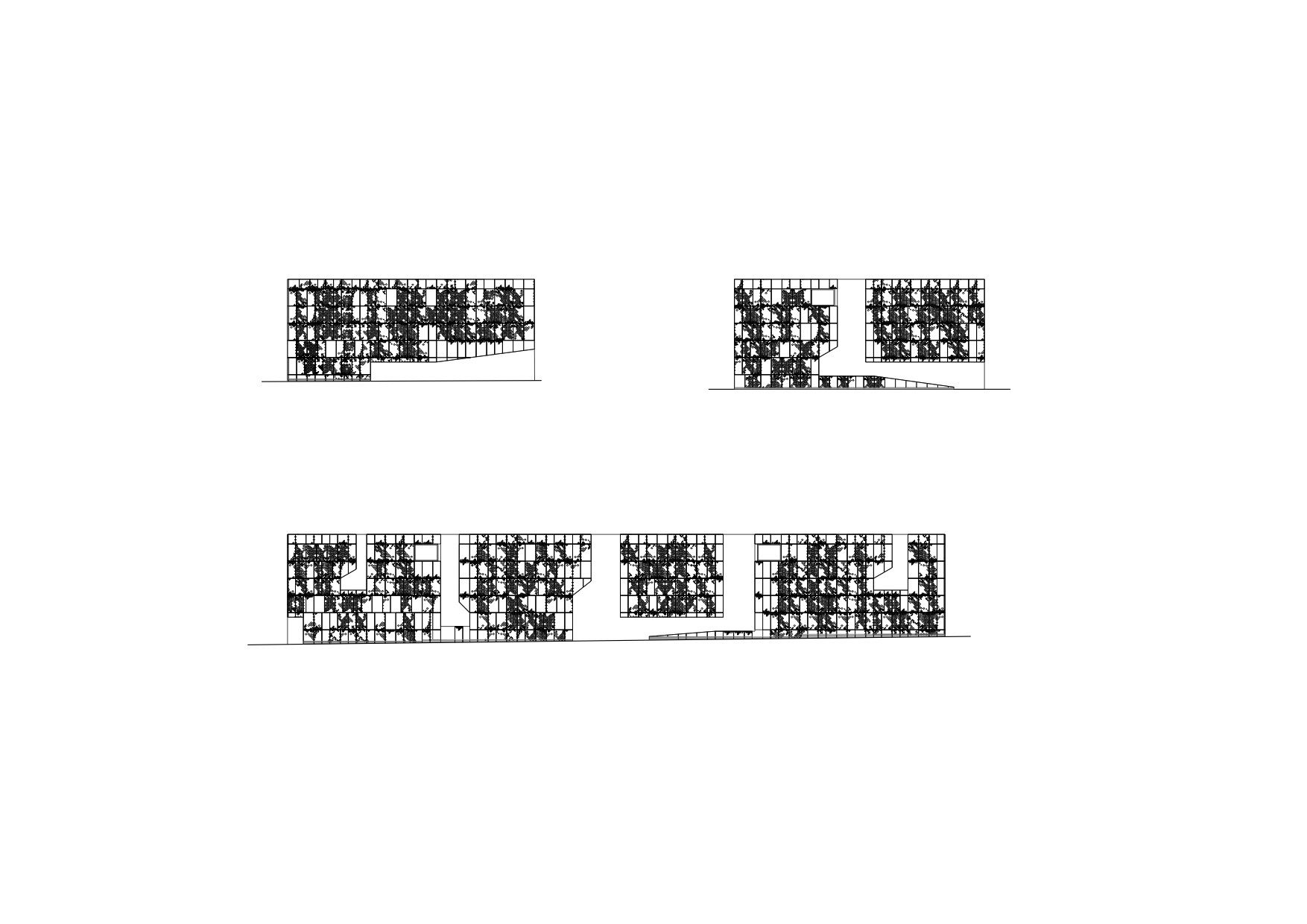

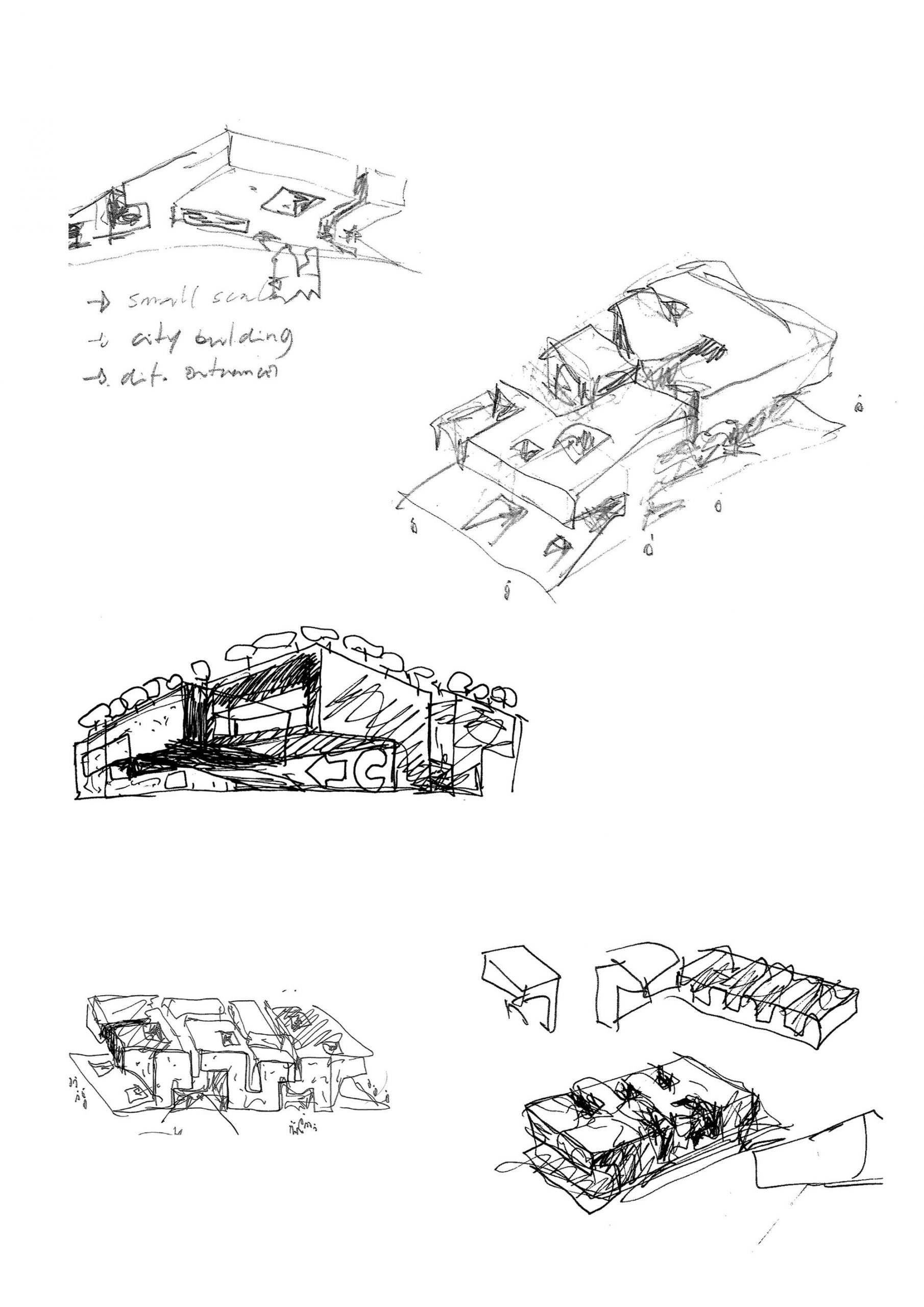

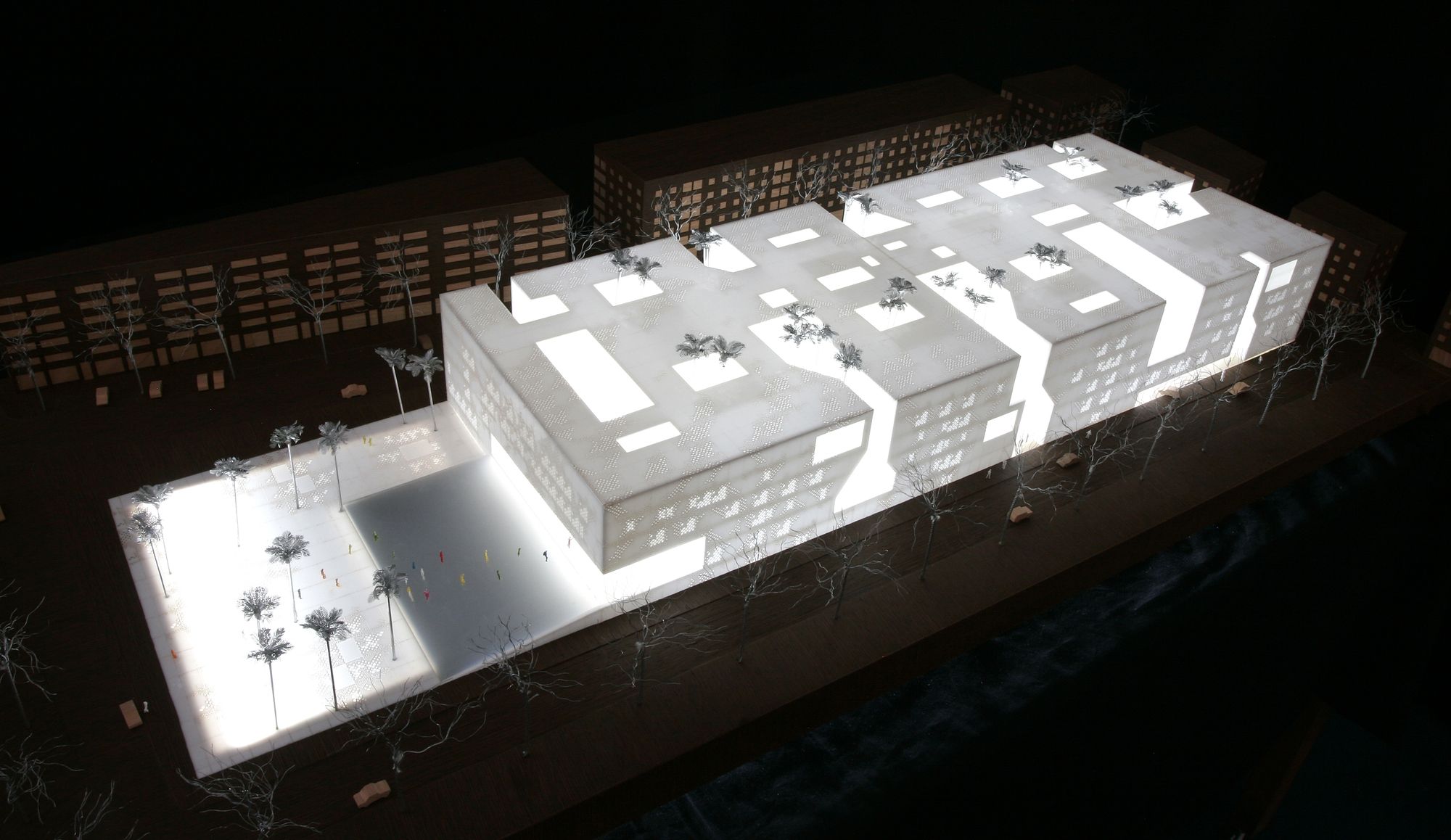

The project could be said to consist of a single, large block that is intersected by courtyards that sometimes extend to the outer perimeter of the building. The chromatic scheme of the building is coherent with this volumetric logic: the outside is white, and the inside of the “subtracted” courtyards is gold-colored.There is one thing one can’t acuse Mecanoo of doing is of not being determined – there is a certain decisiveness in designing a block-wide building, whose spaces are created through a subtraction of volumes.

Inner courtyards are typically moorish. In this building, their function has to do with providing ventilation and illumination to the inner parts of the building, while also serving as an outdoor space that’s sheltered from the outside world. They also feature palm trees that are inserted into big, golden vase-like containers. Yet, it could be that this is the all-so-common vice that architects have to “embellish” their plans, models, renders and drawings with trees, without much consideration. Will these trees “survive” in the middle of such a massive building?

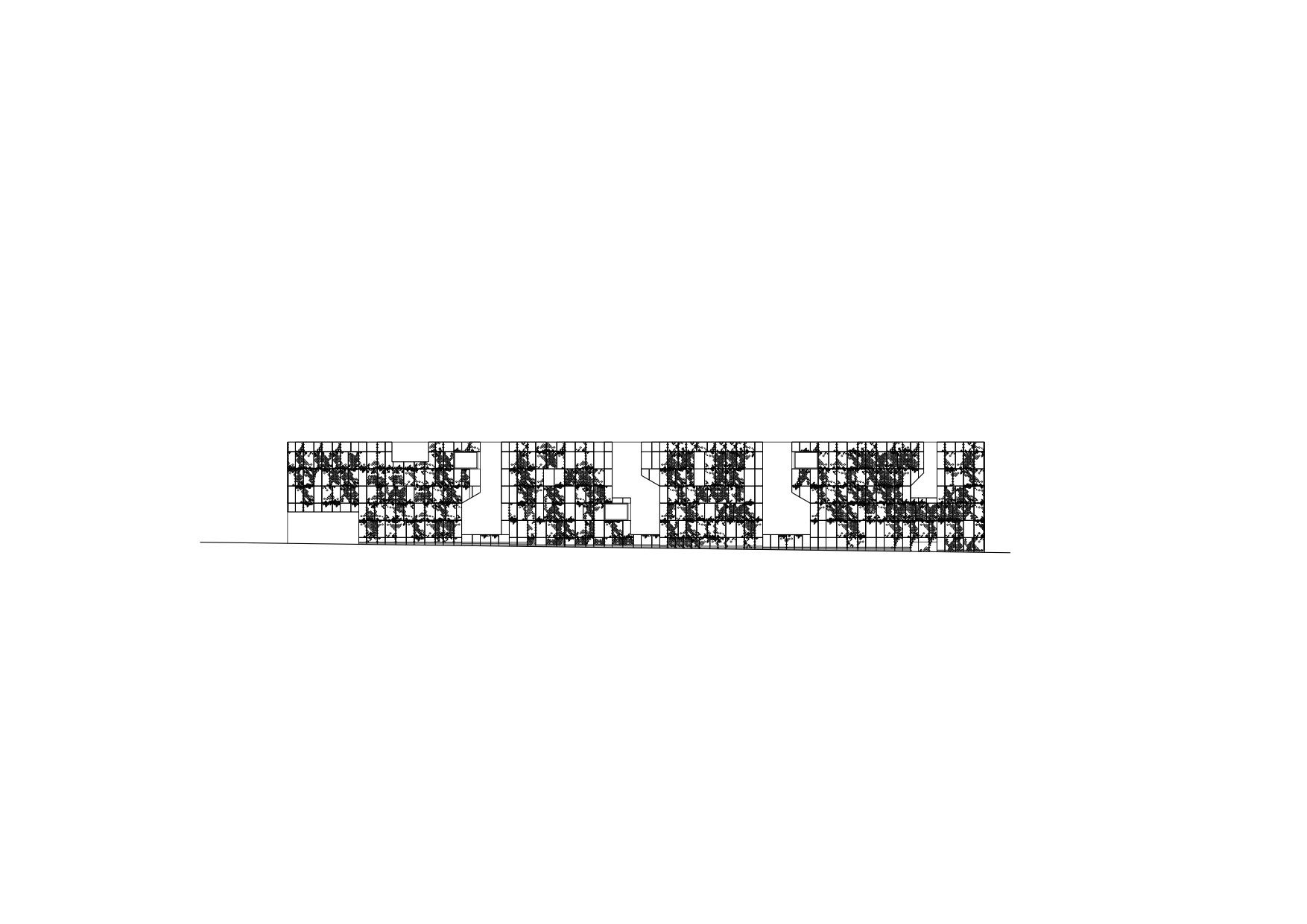

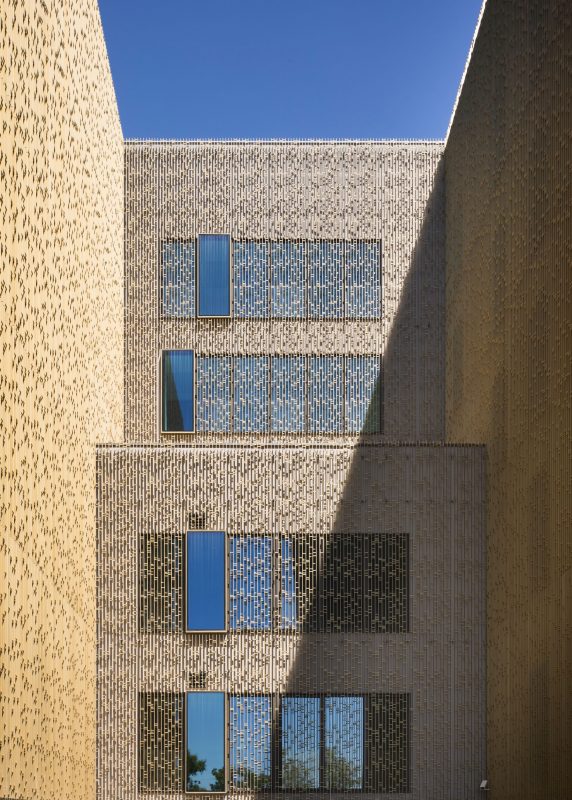

Still on a moorish note, the geometric patterns that occupy parts of the façade are evidently an attempt to reinterpret arabesque, filigree motifs, using contemporary and more minimalist shapes. In fact, for centuries the moors and the islamic civilization has adorned their buildings with abstract and complex motifs. The Palace of Justice attempts to place itself in the continuation of this tradition by using ceramic tiles and holes in the walls. Yet one can’t help but to think about the inherent contradiction relating to this question. If the idea is to invoke a sense of islamic architectural ancestry, then why would one simplify the typical filigrane in this way, using such contemporary shapes?

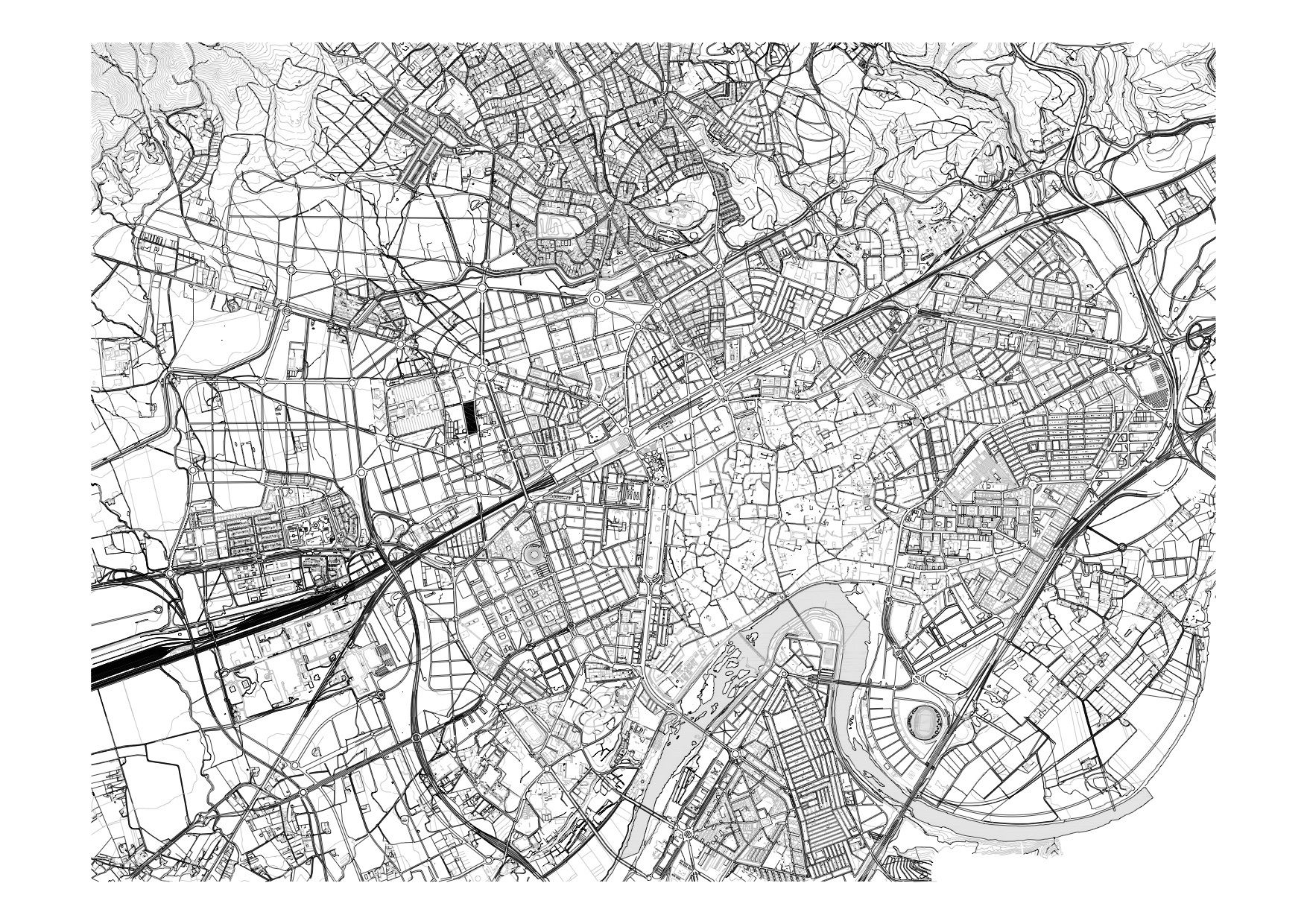

The Palace is also intended to produce a square on its entrance, while organizing its surroundings, the streets and the city block’s conection to the rest of the city. Its organization is distributed in a manner that somewhat highlights its “city within a city” character, which is to say, the fact that its program is a public service. The ground floor contains the courtrooms, a marriage registry and a restaurant – more public uses. In the above floors there are offices and other privacy-requiring programs, while underground one finds the archives and the jail cells. The more “shameful” aspect of justice – the incarceration of human beings as a way to maintain power relations and order in society – is hidden underground, pushed to invisibility, privatized and removed from the consensual, collective gaze. In other words, architecture is inseparable from the discourses of its time, and putting a jail underground is exactly that – a choice to hide the visually unpleasant realities of the social system. The building’s “whiteness” is coherent with this fact, as if it were a dress that hid/presented it with a certain ideological charge – as Mark Wigley would say.

Its permeability on the ground floor makes it a continuation of the public space that it (intentionally) creates on the outside. In fact, it may be the reverse; the square is the continuation of the permeable, acessible ground floor.

A piece of white, sober architecture, of Iberian islamic tradition, perfurated by a contemporary interpretation of arabesque filigrane; a big building, that defines a block, a square and organizes the surrounding areas; a public program, for the service of the citizens – the Palace of Justice has everything to be a working, contextualized and (depending on the taste) beautiful piece of architecture.