Green roofs, extension of landscape, fluid concrete, reflected worlds, austere concrete, surrounding trees. These elements are gracefully incorporated together by Norihiko Dan and Associates, to create the new visitors center for the Sun Moon Lake Hsiangshan area in Taiwan. The sheer amount of thought and description provided by the architect makes any review/description given by me pale in comparison. Thus, below is the description given by Norihiko Dan and Associates and translated by Izumi Tanabe.

This is one of the projects from an international competition held in Taiwan in 2003 for four representative sightseeing locations in Taiwan called the Landform Series. It is a project for an environment management bureau that houses a visitor center in the Sun Moon Lake Hsiangshan area.

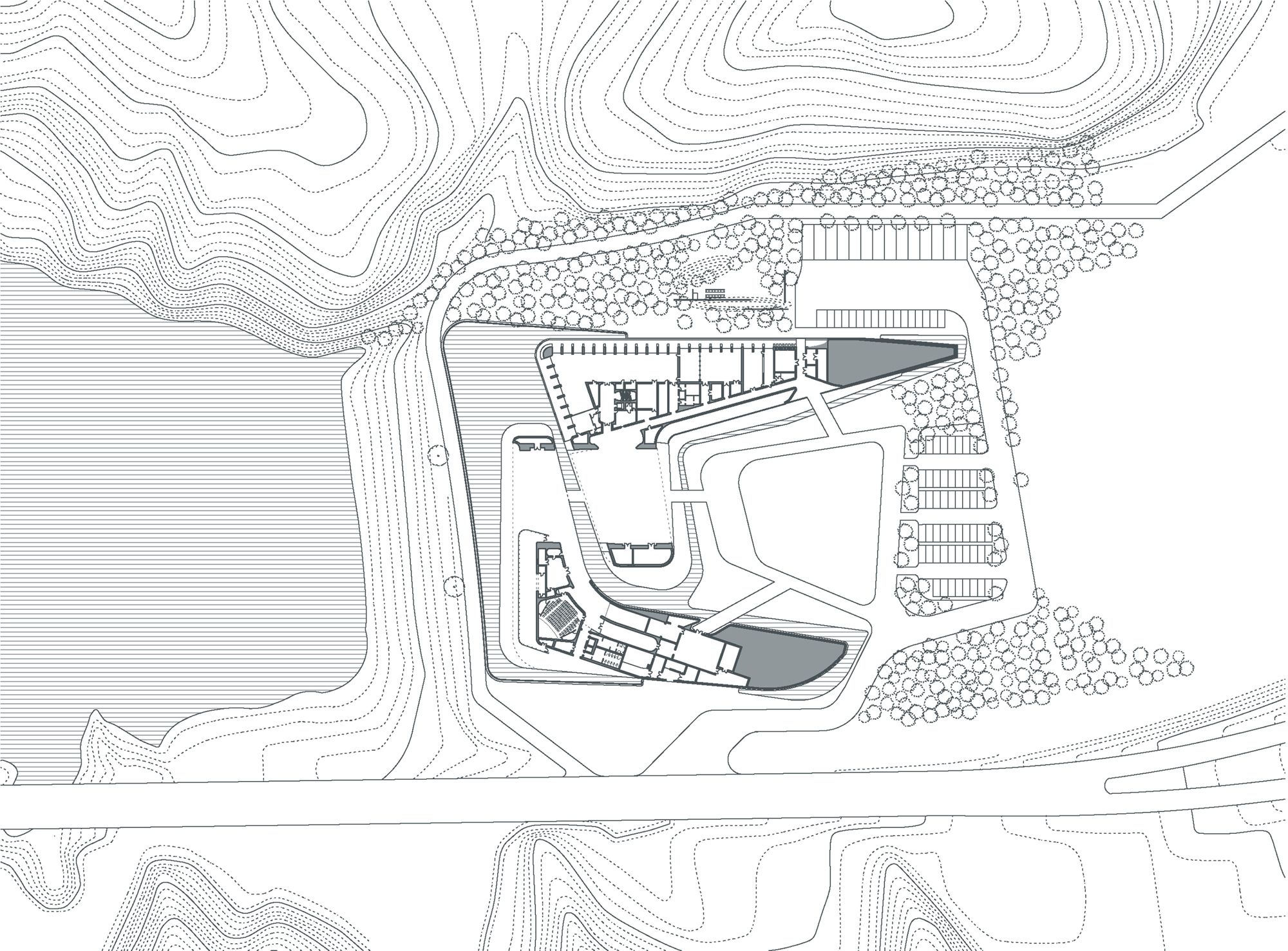

The site just touches the narrow inlet extending almost south-north at its northern tip, has a narrow opening facing the lake-view direction, and extends relatively deep inland along a road. Looking towards the lake, the lake surface looks like it is cutout in a V shape as mountain slopes close in from both sides.

That is, although the site is for the Sun Moon Lake Scenery management bureau, it doesn’t have a 180° view of Sun Moon Lake as can be enjoyed from the windows and terraces of the hotels standing on a typically popular site

That is, although the site is for the Sun Moon Lake Scenery management bureau, it doesn’t have a 180° view of Sun Moon Lake as can be enjoyed from the windows and terraces of the hotels standing on a typically popular site

In most cases with sites like this, the building is positioned on the lake side to secure the greatest view possible, and thus the inland side tends to become a kind of dead space.

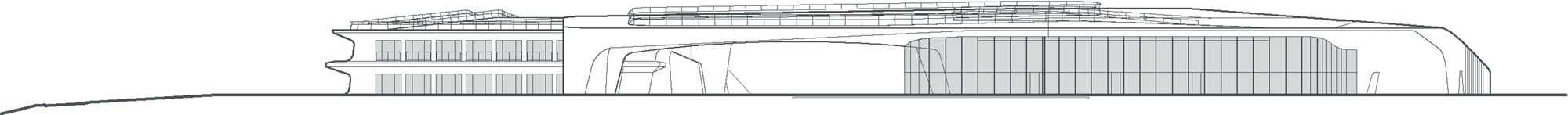

As the basic policy for the design, my first aim was to propose a new model for a relationship between the building and its natural environment while preserving the surrounding scenery and keeping the inland area from becoming dead space. My second priority was to address the disadvantages of the site whose view of the Sun Moon Lake is not necessarily perfect, and to draw out and amplify the potential advantages. One way to solve the first problem was to pursue a new relationship between the building and its surrounding landform. Since long ago, buildings have generally been built “on” landforms, but there have been cases in which they have been built within landforms, such as the early Catholic monasteries of Cappadocia and the Yao Tong settlements along the Yellow River, and there have also been such classics as Nolli’s map that considered the building as the ground which can be curved or transformed, similarly to the landform, in a conceptual sense. Due to the fact early modernism negated in totality the methods of self-transformation—including the poche method that belonged to pre-19th century neoclassicism in particular—and demonstrated an inability to adapt to the complex and diverse topography in such areas as east Asia, I believe that 20th century architecture actually gave rise to the phenomenon of land development projects that “flattened” mountains, an approach that is almost synonymous with the destruction of nature.”]

As the basic policy for the design, my first aim was to propose a new model for a relationship between the building and its natural environment while preserving the surrounding scenery and keeping the inland area from becoming dead space. My second priority was to address the disadvantages of the site whose view of the Sun Moon Lake is not necessarily perfect, and to draw out and amplify the potential advantages. One way to solve the first problem was to pursue a new relationship between the building and its surrounding landform. Since long ago, buildings have generally been built “on” landforms, but there have been cases in which they have been built within landforms, such as the early Catholic monasteries of Cappadocia and the Yao Tong settlements along the Yellow River, and there have also been such classics as Nolli’s map that considered the building as the ground which can be curved or transformed, similarly to the landform, in a conceptual sense. Due to the fact early modernism negated in totality the methods of self-transformation—including the poche method that belonged to pre-19th century neoclassicism in particular—and demonstrated an inability to adapt to the complex and diverse topography in such areas as east Asia, I believe that 20th century architecture actually gave rise to the phenomenon of land development projects that “flattened” mountains, an approach that is almost synonymous with the destruction of nature.”]

In fact, the very key to linking buildings with landforms lies in these issues that have been ignored by modernism.

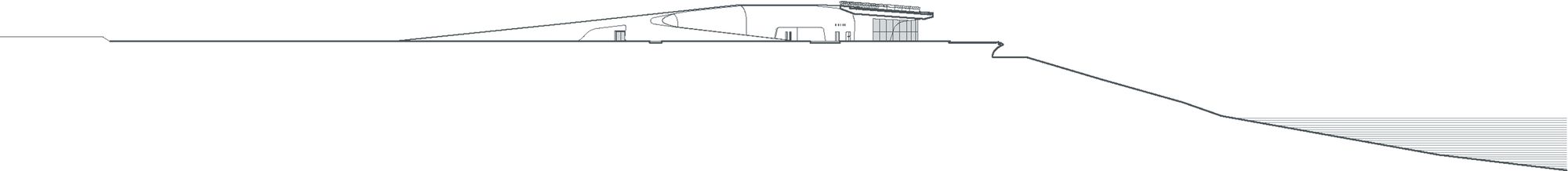

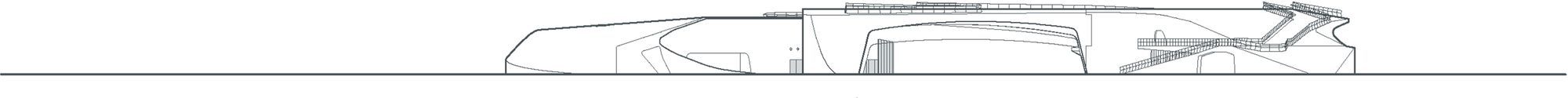

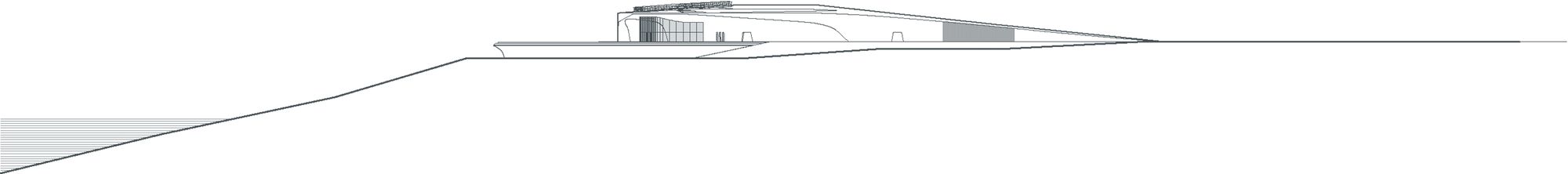

In this project, in order to emphasize a sense of horizontality to the architecture, I added more soil taken from construction for the foundation to the volume of the building conventionally required, and designed a composition in which the building on the lake side and a sloping mound on the inland side are in gradual and continuous transition.

In this project, in order to emphasize a sense of horizontality to the architecture, I added more soil taken from construction for the foundation to the volume of the building conventionally required, and designed a composition in which the building on the lake side and a sloping mound on the inland side are in gradual and continuous transition.

By adopting this composition I planned the design so that continuity is regained between the building and the landform to form an integrated garden rather than having the building sever the landform.

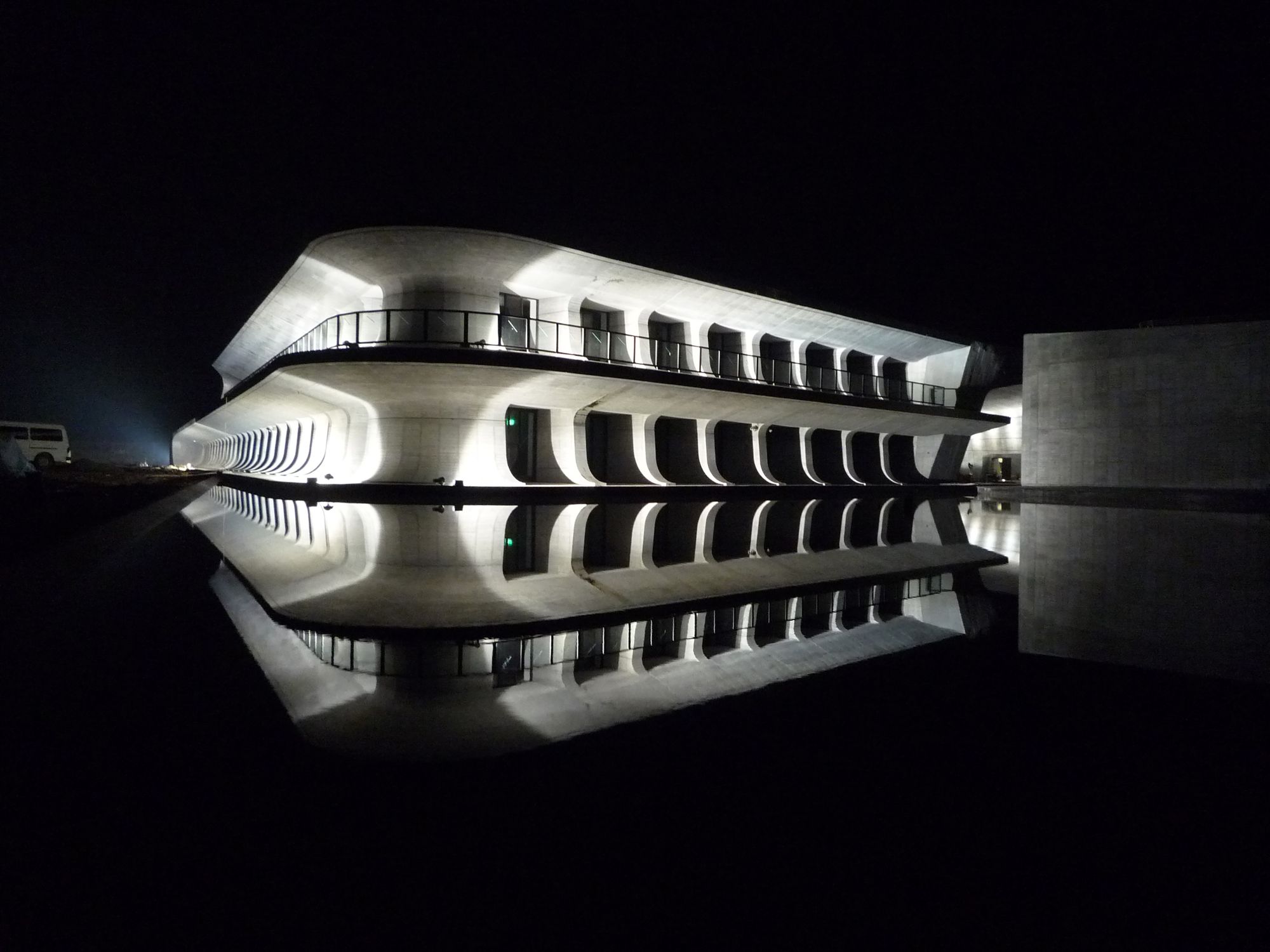

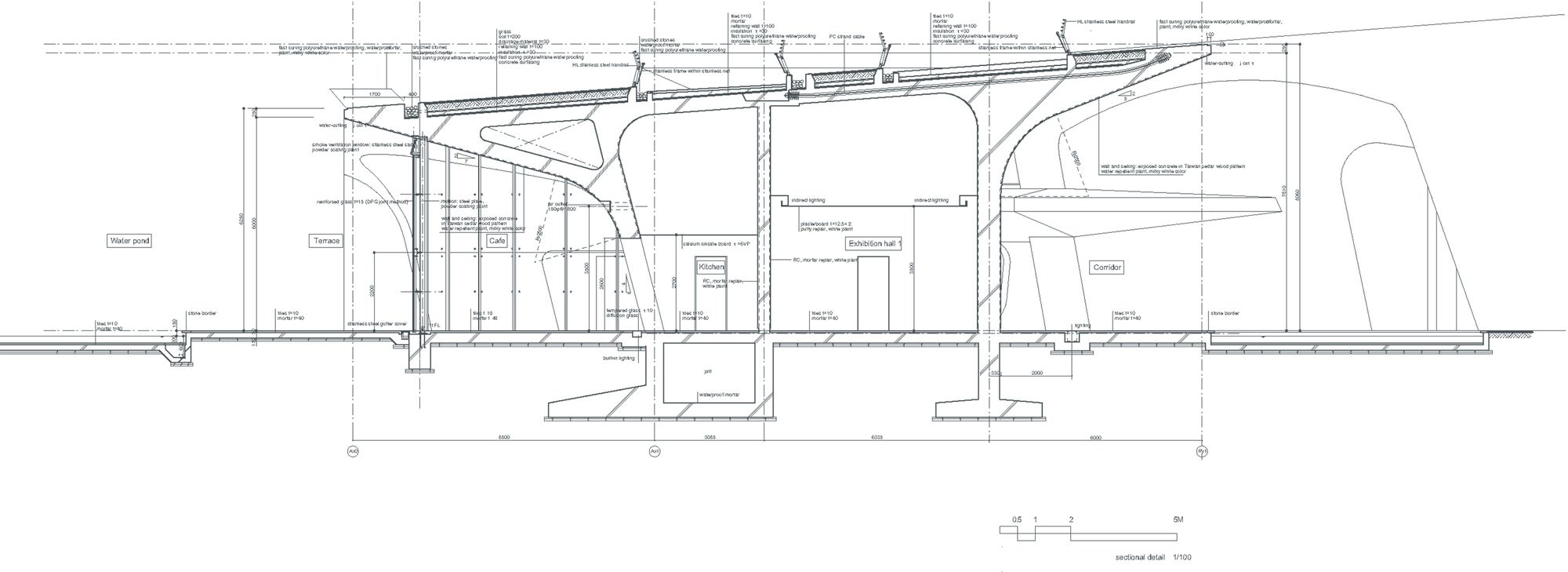

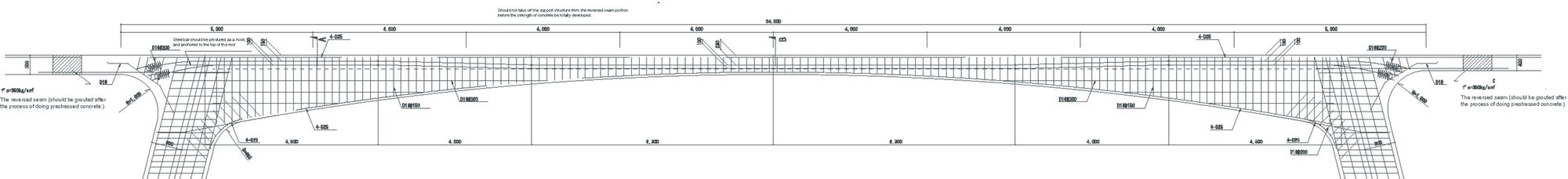

For the second theme, I designed an extensive axial layout by rerouting the approach flow-line from the road to that it extends far inland and then curving it back as far as possible via two large arches spanning 35 meters each, to create a sense of dynamism that leads to the lake surface. Moreover, I set up a near-view water basin in contrast with the distant-view lake surface to enhance the water surface effect by mirroring the distant view upon it.”]

The fact it is only possible to view the lake surface distantly from a relatively narrow angle means that the site—fortunately free of nearby buildings—is surrounded 360° by a lush sea of trees.

I saw this as the second undulating surface and opened up the upper part of the building by greening it to create continuity with the natural surroundings

These two surfaces—the union of the lake and water basin surfaces, and the resonance of the building’s greenery on the upper part with the surrounding undulating sea of trees—are connected via the tunnel-shaped diagonal path that cuts and penetrates through the interior of the building, and through the slopes carved into the building like mountain paths, to create a multitiered landform.

This half-architectural and half-landform project is conceptualized as a stage setting to bring out and amplify a hidden dimension of the scenery and environment of Sun Moon Lake, and at the same time create a new dialogue between the human being and nature that provides another new dimension to this area.