Government-funded public housing began with a common dream: to end slum life with safe affordable housing. Instead, most of these projects became synonymous with the city’s poverty and crime.

We usually only study the successful public housing projects, but it’s equally, if not more, important that we study the unsuccessful ones as well, so we don’t repeat the same mistakes in our designs. Check out the World’s 3 Utterly Unsuccessful Public Housing Projects to know What Not to Do.

3 Utterly Unsuccessful Public Housing Projects

1. Cabrini-Green Public Housing, Chicago

Cabrini-Green was a public housing development located near a flame-spewing gas refinery which gave it its nickname, the hellhole! It initiated a few row houses and eventually had eight 15-storey towers covering a land area of 283,280 m2. In total, the gigantic complex had 3,607 units which housed over 15,000 residents.

The government prioritized the poorest people, including single mothers and the homeless, to access housing. The project was a symbol of hope for mitigating slum life but soon became a high-rise slum itself. Cost-reducing measures taken during construction led to quick deterioration.

Although original residents were the Italian families (who inhabited the land before), the housing later became exclusively black. Due to the racial biases in Chicago at the time, the maintenance funds were denied and deterioration furthered. Dumpsters started overfilling and no one cared to fix anything. All kinds of social ills spread throughout the complex in no time. Gangs took over public spaces and drug dealers started preying on the young. More tenants became fearful to leave their homes. Crime soared further with working residents becoming unemployed as the nearby factories closed.

Since then, Cabrini-Green made the greatest record of poverty-stricken crime conditions than any of Chicago’s housing projects.

“a virtual war zone, the kind of place where little boys were gunned down on their way to school and little girls were sexually assaulted and left dead in the stairwells” – USA Today

Finally, in the late ’90s, the government issued orders to demolish these public housing buildings and set a new program. The last high-rise bits came down in 2011, but we still don’t know if the housing authority kept its promise of finding new homes for the residents.

2. Pruitt-Igoe Public Housing, St. Louis

If you ever think of going vertical for housing the homeless refugees, your critics will use Pruitt-Igoe to defeat you. After World War II, the homeless population surged throughout the US. The major city of St. Louis, particularly, had a rapid increase in slums. Therefore, the government decided to fund the mass-production of public housing to get people out of inhumane conditions. Rather than eradicating ghettos, Pruitt-Igoe became the stage for hosting city crime.

Japanese-American architect, Minoru Yamasaki, first proposed a mixed-rise cluster of buildings, but the public housing administration objected to its pricing and insisted on building cost-cutting uniform towers. Thus, they erected 33 racially segregated 11-storey high-rises on 230,000 m2 cleared of the city fabric. These public housing buildings appeared utterly alien to the surrounding low-lying buildings.

Restricted budgets resulted in poor building quality and cheap fixtures. However, the project seemed to offer every luxury that slums lacked: electricity, plumbing, green spaces, etc. Within a decade, just the poor black tenants inhabited Pruitt-Igoe. Thereafter, the project became hard to maintain. Heaters, toilets, garbage incinerators, electricity, all started malfunctioning. The government didn’t assist, and the public didn’t care.

By the mid-’60s, the crime rate greatly soared while living conditions declined. Skip-stop elevators stopped every 3 floors, making the stairwells an opportunity to rob residents as they moved between the elevator floors. One time, loud gags echoed from the buildings as faulty plumbing broke, letting all raw sewage loose on the hallway walls and floors. This event marked a major call for demolition.

In 1976, the municipality demolished the housing on live media. Thereupon, Charles Jencks, an architectural historian, regarded Pruitt Igoe’s doom as a failure of architecture to solve social problems.

3. Pink Houses, NY, Brooklyn

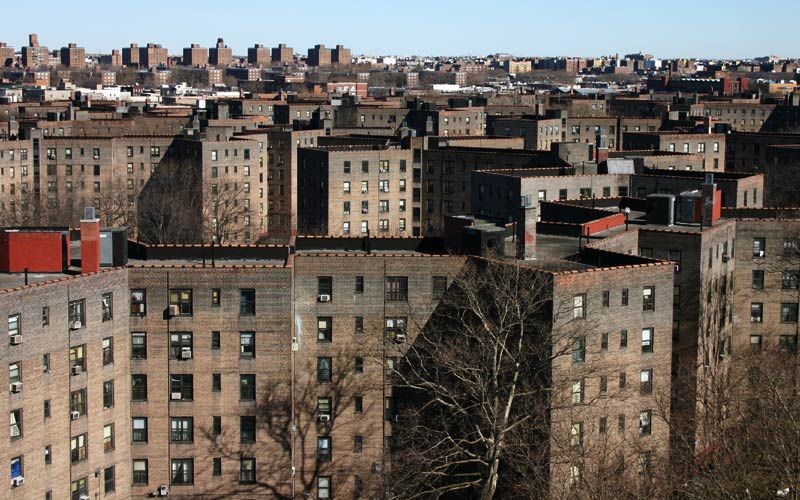

If you want someone to shoot you dead, visit Pink Houses! Pink Houses, also known as ‘the pinks’, are brick towers around concrete pathways. They are 22 eight-storey buildings with 1500 apartments. Apart from the pink equipment in abandoned public spaces and pink signboards from NYC Housing Authority, the housing project is colorless.

Courtesy of NYCHA

The project is isolated from the urban fabric and hence completely neglected by the city. Patrol officers and cooks at the nearby restaurants are the only people with jobs. Earl Greggs, who lives on the 3rd floor, reveals the extent of negligence that the housing project suffers:

“Work does not get done until someone gets killed.”

This statement cannot be truer for a place where no one cared to fix a lightbulb until an officer shot a man in an unlit stairwell. Residents were moved by this shooting but they weren’t shocked; they had been complaining about the conditions for years.

Dark stairwells and neglected conditions make fertile ground for crime to sprout, and this is exactly what happened. Moreover, the constant presence of rifles and guns creates a dangerous environment for residents and officers alike. Stairwells are the unsafest places in this public housing project yet impossible to avoid due to regularly malfunctioning elevators. To top it, security cameras are not put where they are most needed i.e. in places where drug dealers and the homeless hang out.

In 2005, a gang called ‘pink houses crew’ became infamous for robbing jewelry stores and dropping badly beaten bodies along the expressway. As a result, the residents became very afraid to step out of their houses in the evening. Trash piles up in front of the housing faster than it can be removed which produces an overwhelming smell throughout the complex. Pink houses are not demolished and continue to spread further horrors.

What Do We Learn?

These events made people give up the idea that architecture could alleviate poverty. Things might not have ended the way they did if architects used the budget wisely and planned the maintenance. We should try to build such projects with the acceptance of the users as per their needs so they can find real homes in these structures. Aravena’s ‘Half a House’ approach is a good example. Architects should also consider building public housing in city centers to create safer environments. Lastly, going high-rise has always been a bad approach for public housing projects. Stay low, folks!