It’s been a couple of years now since I heard Argentinean architect Rafael Iglesia describe one of his projects as the attempt to produce a thing, not an object. A thing, he said, does not have a project, it has not been designed, but an object has.

I might have misunderstood what he meant, but I translated it as the difference between a chair and a stone. A chair is designed to be able to sit on it. A stone, if of the right size and form, may allow sitting on it, but was not designed as such. A thing has a life on its own, it has no purpose; only circumstances, e.i. use, make a thing become intentional.

Even though it might seem a paradox, the idea of designing a building as if it has not been designed remained in my mind. I wanted to achieve the status of those cases that are closer to nature than to artifice, even though they are obviously manmade, cases in which the consecutive layers of knowledge applied to a given question and the uninterrupted trial and error approach besieging a problem, have shaped answers efficiently and smoothly. Some archaic shoes, some antique vases or some primitive tools have erased the traces of their formation process up to the point of acquiring the capacity to fit life, naturally.

Even though it might seem a paradox, the idea of designing a building as if it has not been designed remained in my mind. I wanted to achieve the status of those cases that are closer to nature than to artifice, even though they are obviously manmade, cases in which the consecutive layers of knowledge applied to a given question and the uninterrupted trial and error approach besieging a problem, have shaped answers efficiently and smoothly. Some archaic shoes, some antique vases or some primitive tools have erased the traces of their formation process up to the point of acquiring the capacity to fit life, naturally.

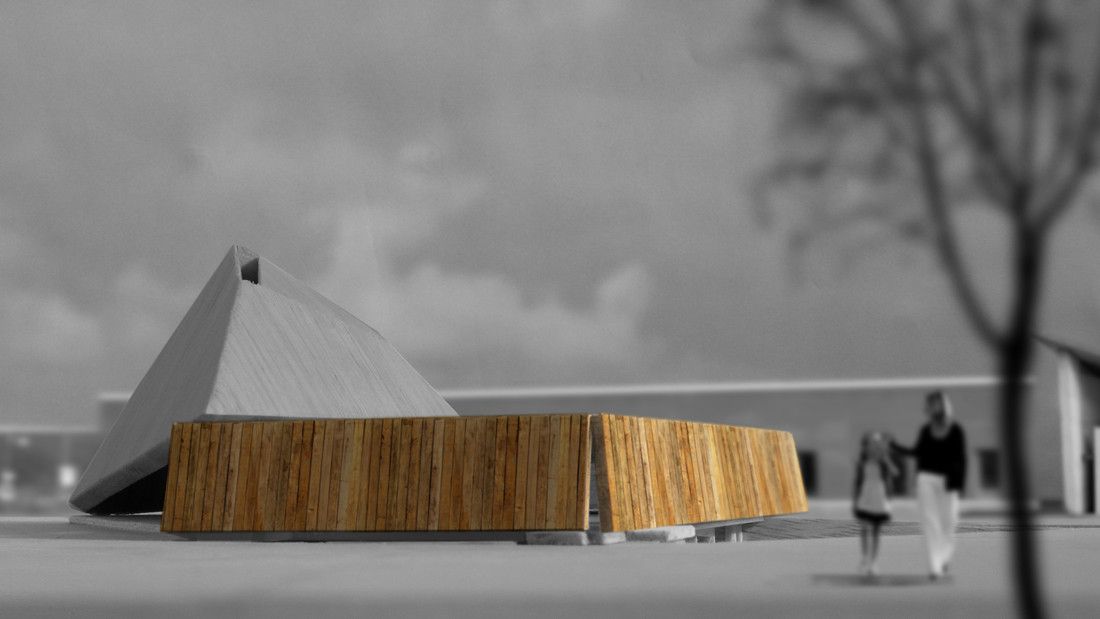

The VITRA job seemed from the very beginning to be the case to do a thing, not an object, something as natural and statement-free as a stone, but if of the appropriate size and form, able to perform as a building, in this case as a children workshop.

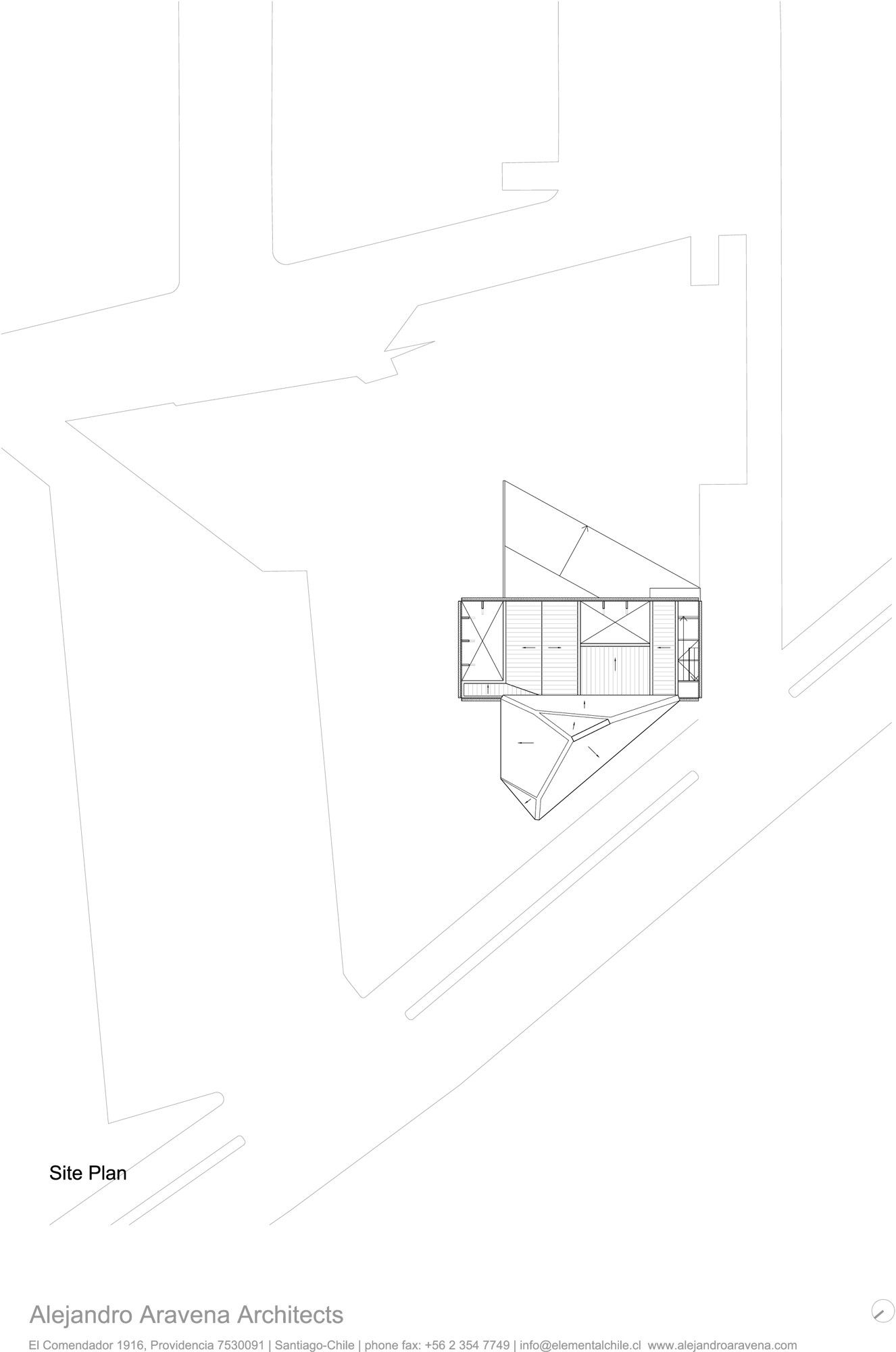

The first meeting took place in November 2007, on-site: an existing garage neighboring Siza’s factory and Hadid’s fire station, that had been recently added to the Weil am Rhein Campus property. Rolf Felhbaum began by saying, as if it was a very normal thing, that he wanted a “direct” building for hosting the workshops that VITRA offers to children as an extracurricular activity. He did not say simple, nor cheap, but direct. It was one of the healthiest and most strategic starts I have ever had. Looking back, that first requirement, became the frame that defined the tone of the discussion and oriented the decisions that were taken afterward.

The first meeting took place in November 2007, on-site: an existing garage neighboring Siza’s factory and Hadid’s fire station, that had been recently added to the Weil am Rhein Campus property. Rolf Felhbaum began by saying, as if it was a very normal thing, that he wanted a “direct” building for hosting the workshops that VITRA offers to children as an extracurricular activity. He did not say simple, nor cheap, but direct. It was one of the healthiest and most strategic starts I have ever had. Looking back, that first requirement, became the frame that defined the tone of the discussion and oriented the decisions that were taken afterward.

In part due to the remoteness (Chile-Switzerland), in part because it just happened that way, we started a “thinking-out-loud” type of process: an Internet dialogue in the form of texts and drawings where very clear, common sense, pragmatic options were evaluated. It was an exchange of facts, not ideas. Ideas are overrated.

Do we keep the garage and adapt it for the workshops? Being the building just a collection of small additions not flexible enough for easy reuse, and being the environmental standard of the construction very poor, insufficient for an educational facility and very costly for a simple upgrade, what appeared to be more reasonable, was to demolish the existing structure.

Do we keep the garage and adapt it for the workshops? Being the building just a collection of small additions not flexible enough for easy reuse, and being the environmental standard of the construction very poor, insufficient for an educational facility and very costly for a simple upgrade, what appeared to be more reasonable, was to demolish the existing structure.

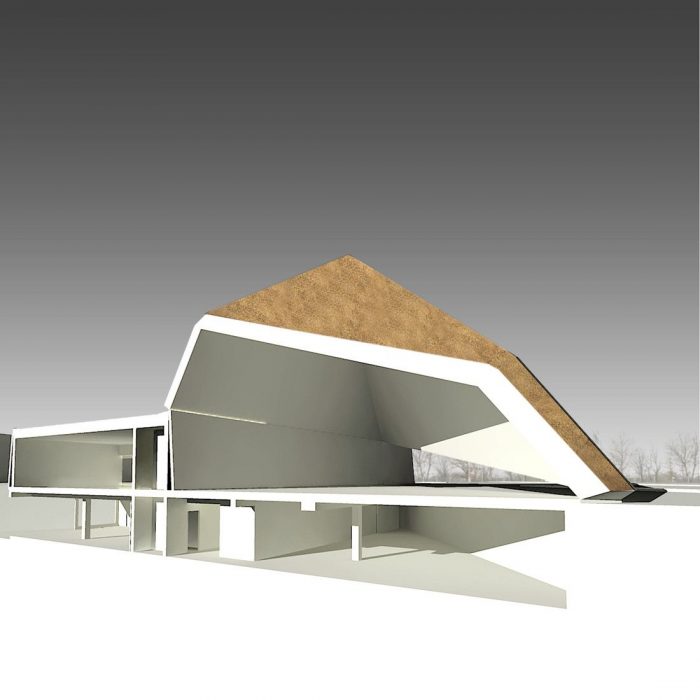

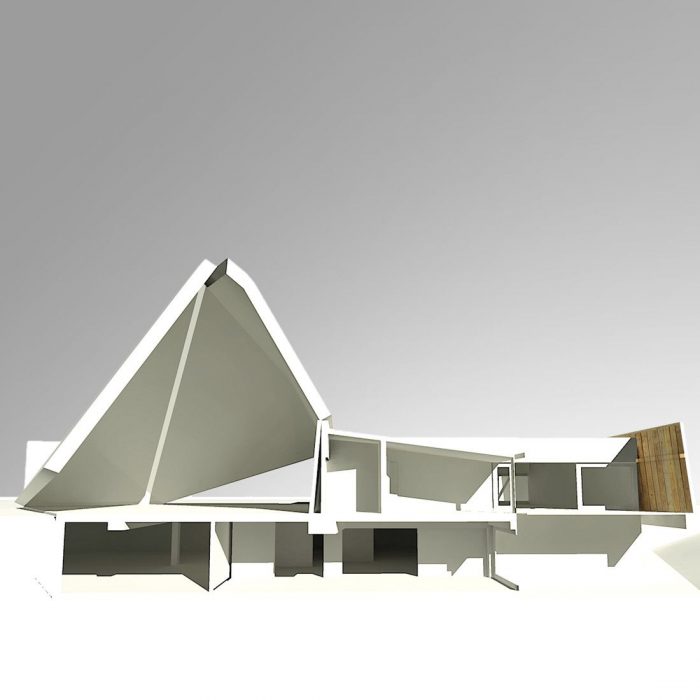

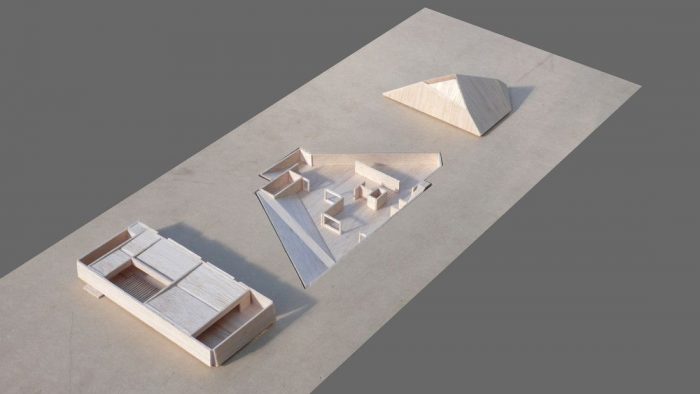

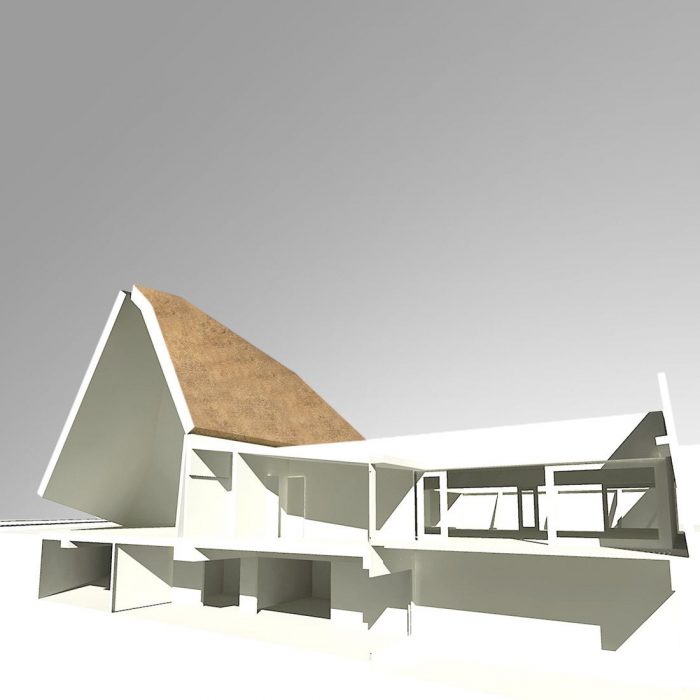

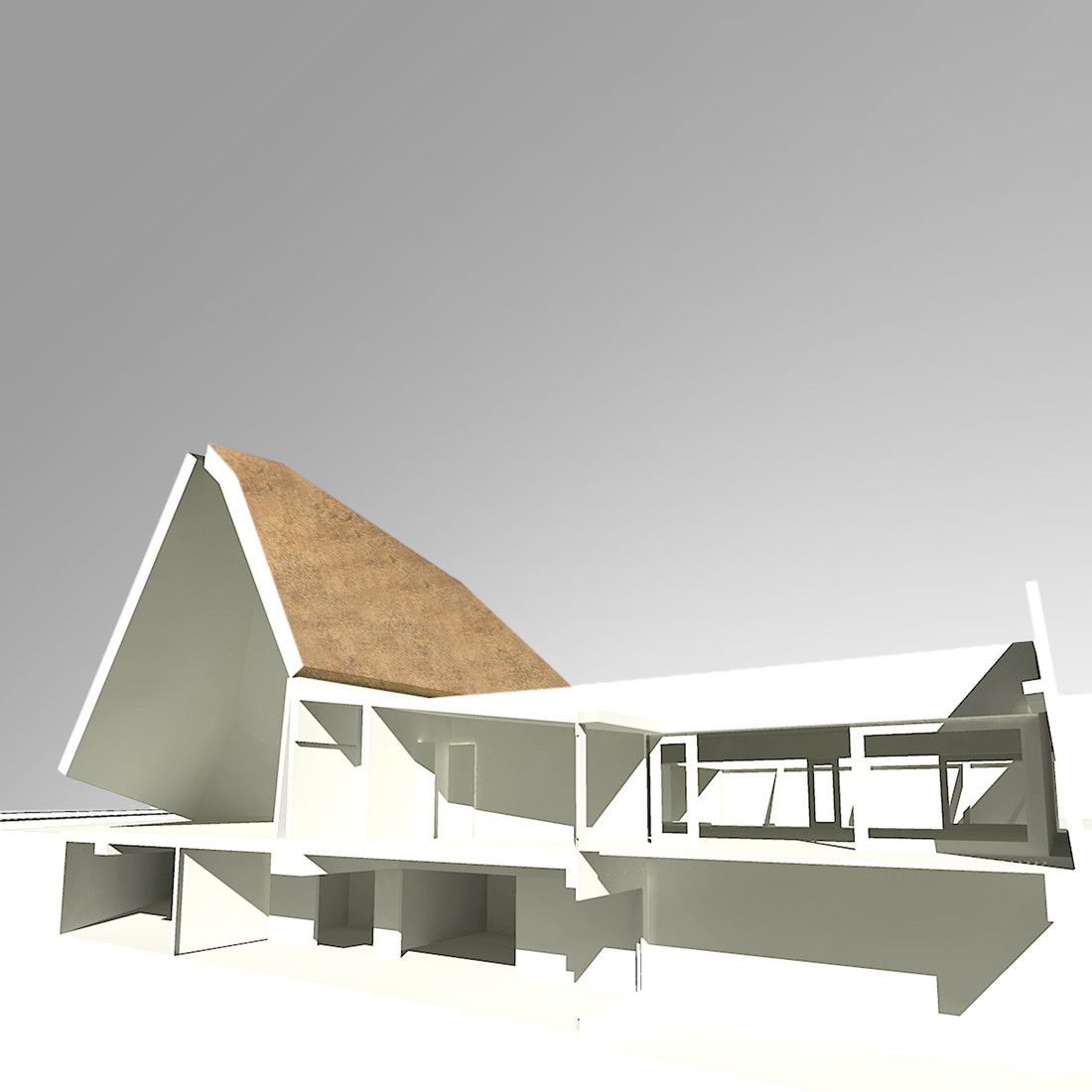

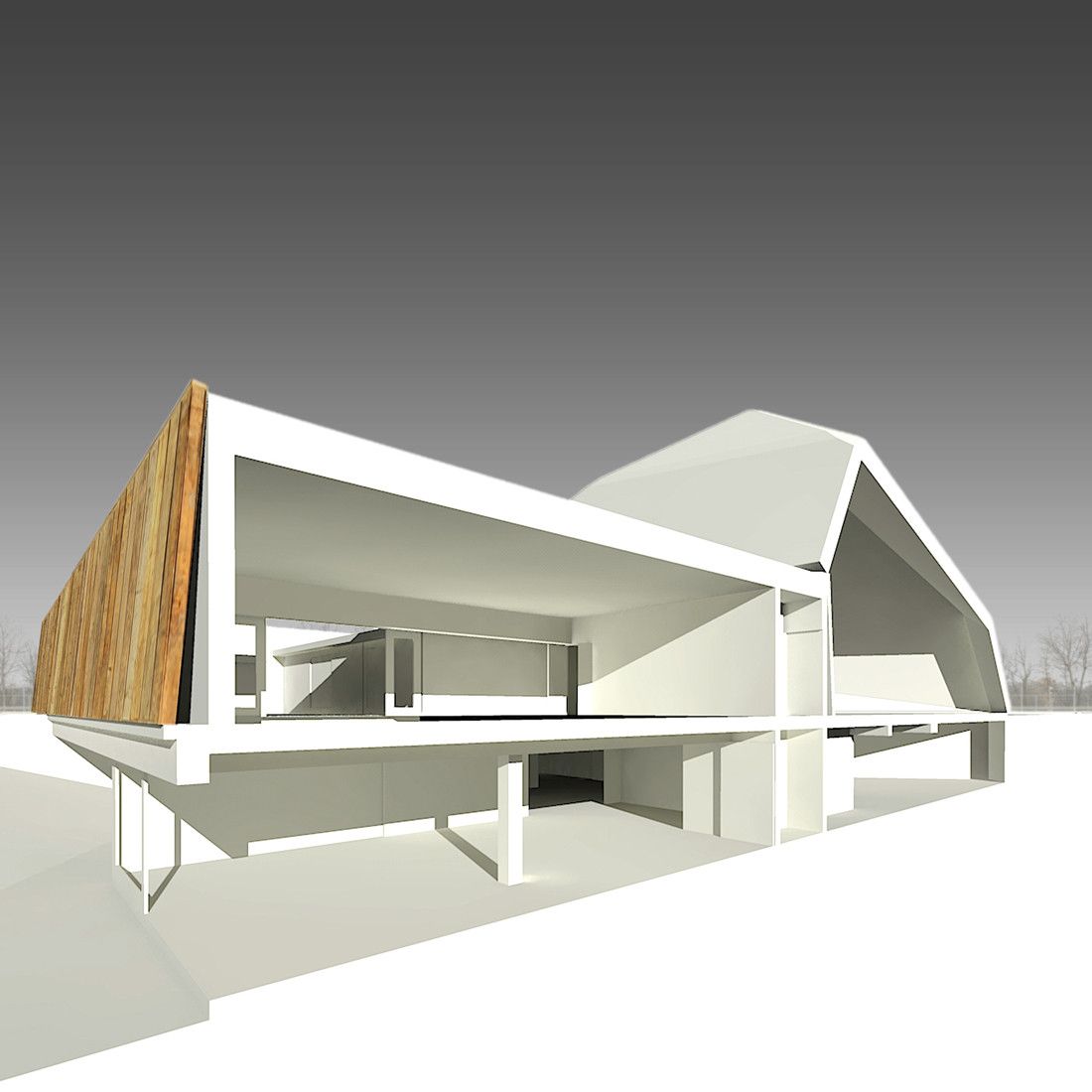

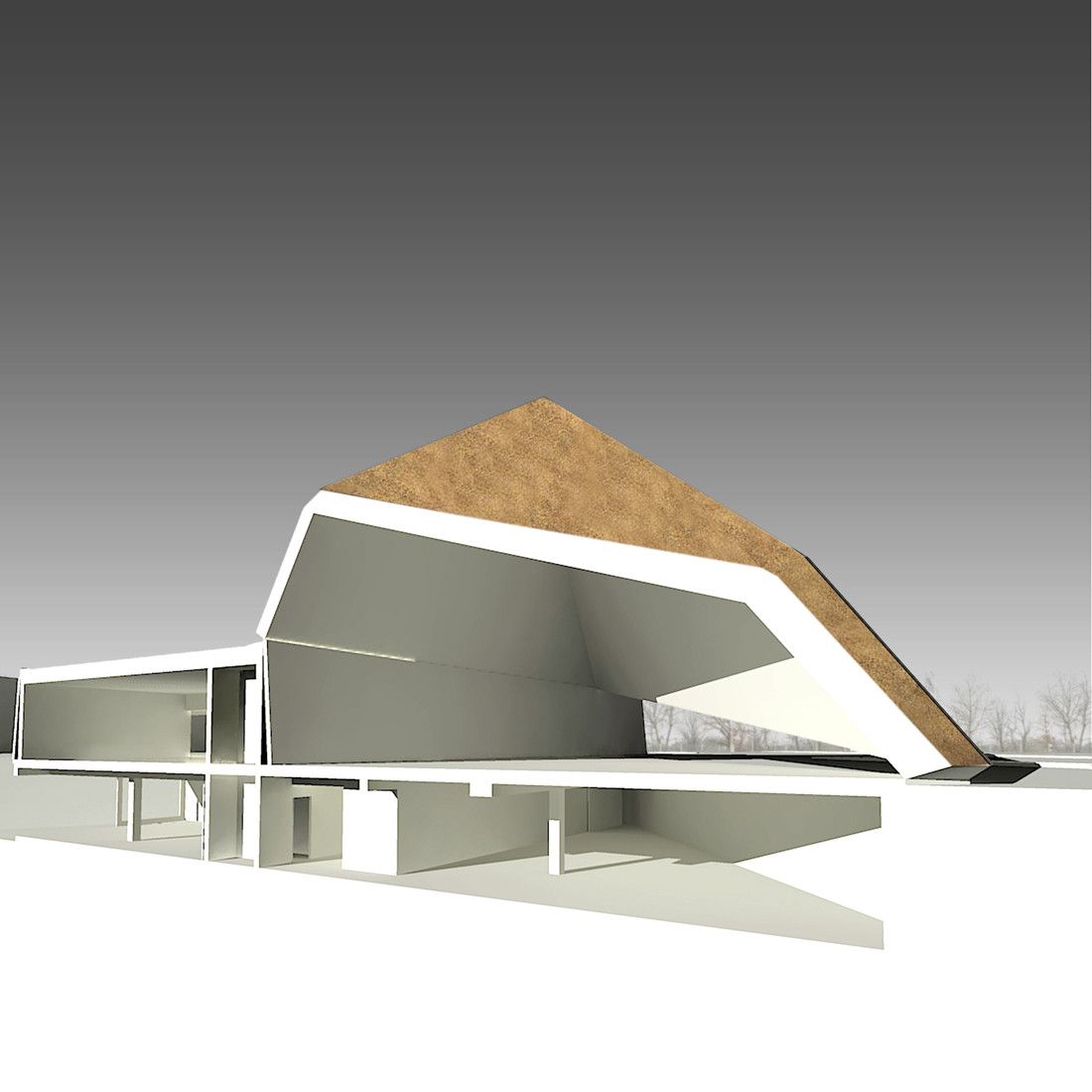

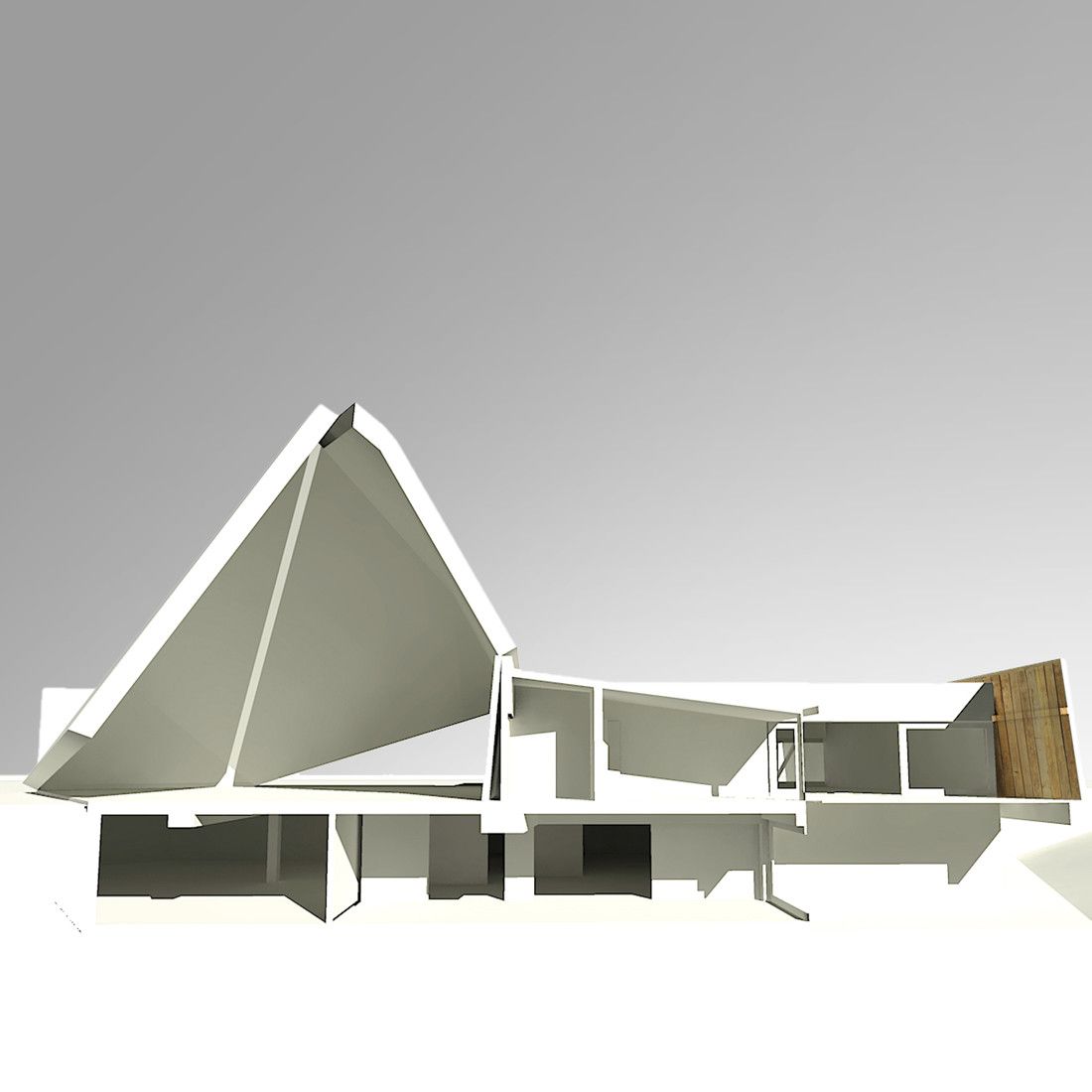

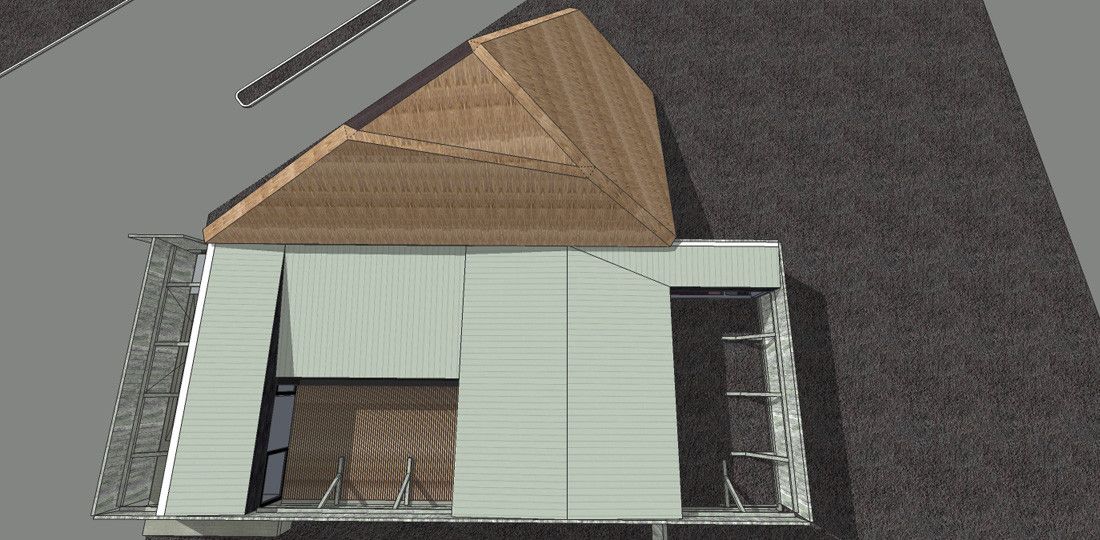

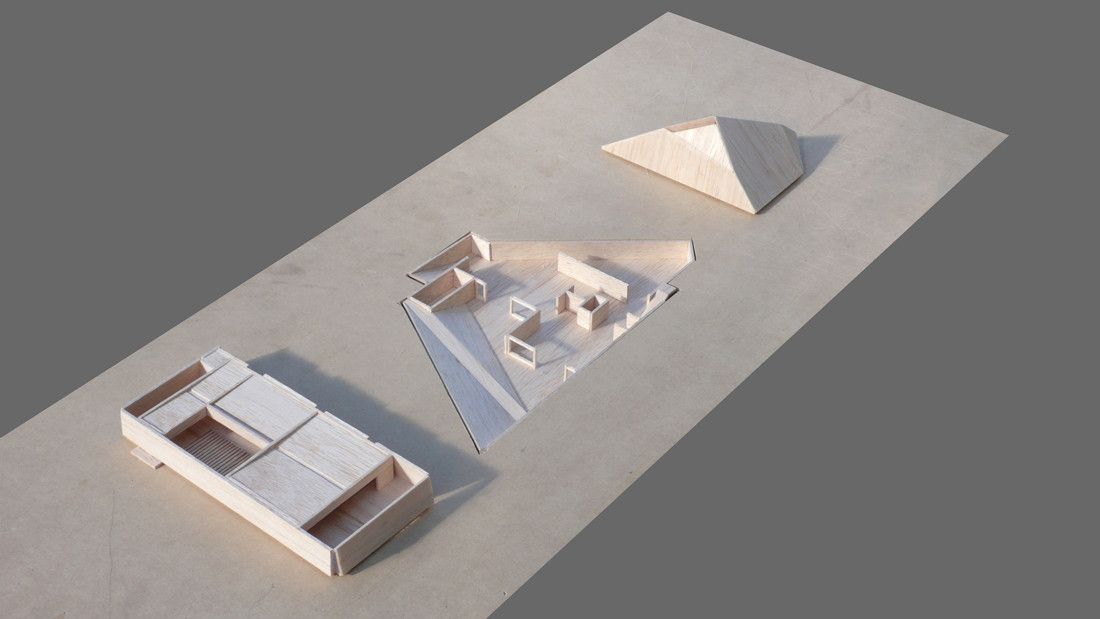

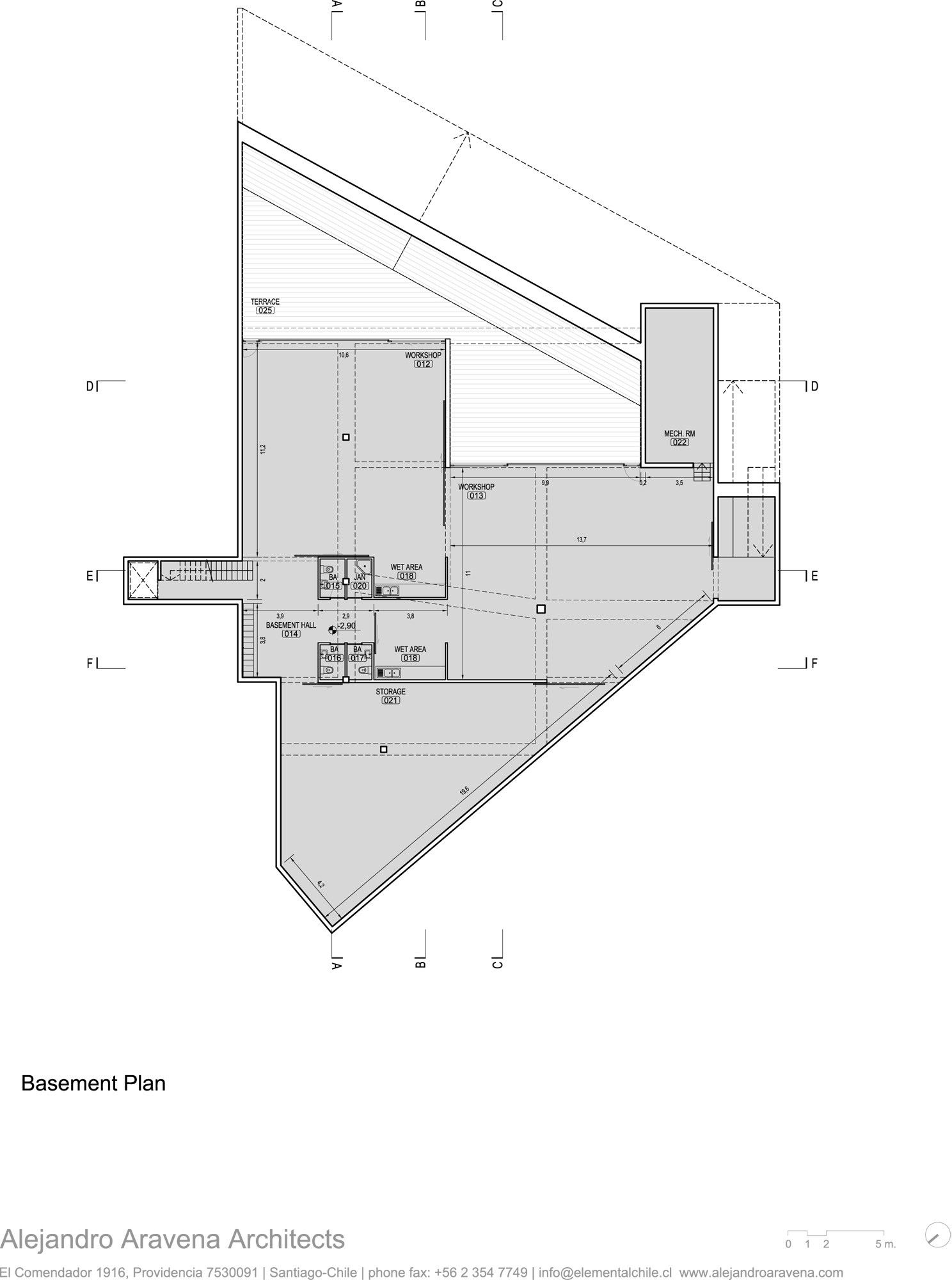

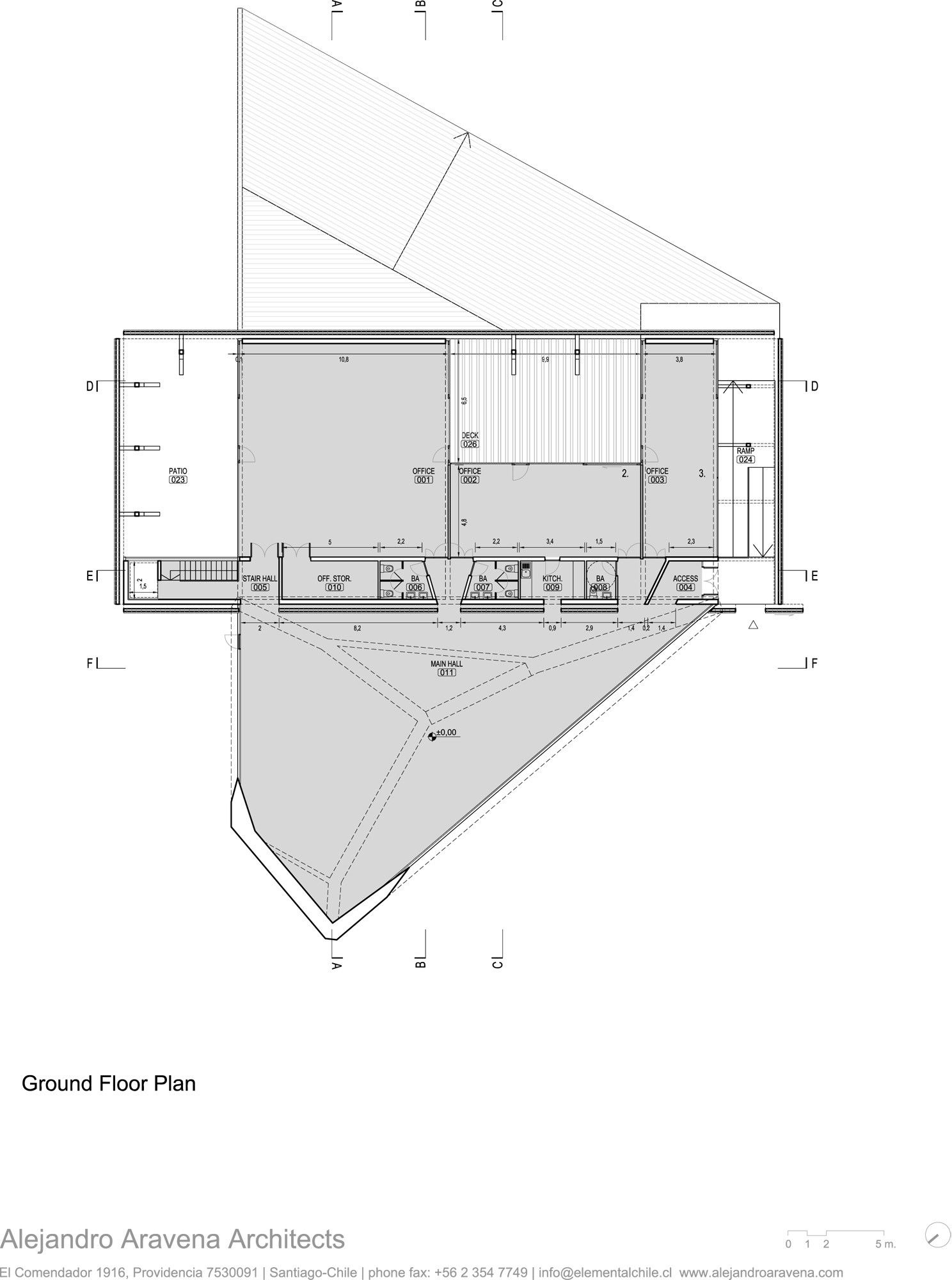

However, to keep the 400 m2 underground made a lot of sense. So, the footprint of the basement dictated the shape of the building on top.

Do we integrate the basement by perforating the slab? To remove some earth and get rid of a peripheral wall to bring light, air, and people through a sloped courtyard, was easier.

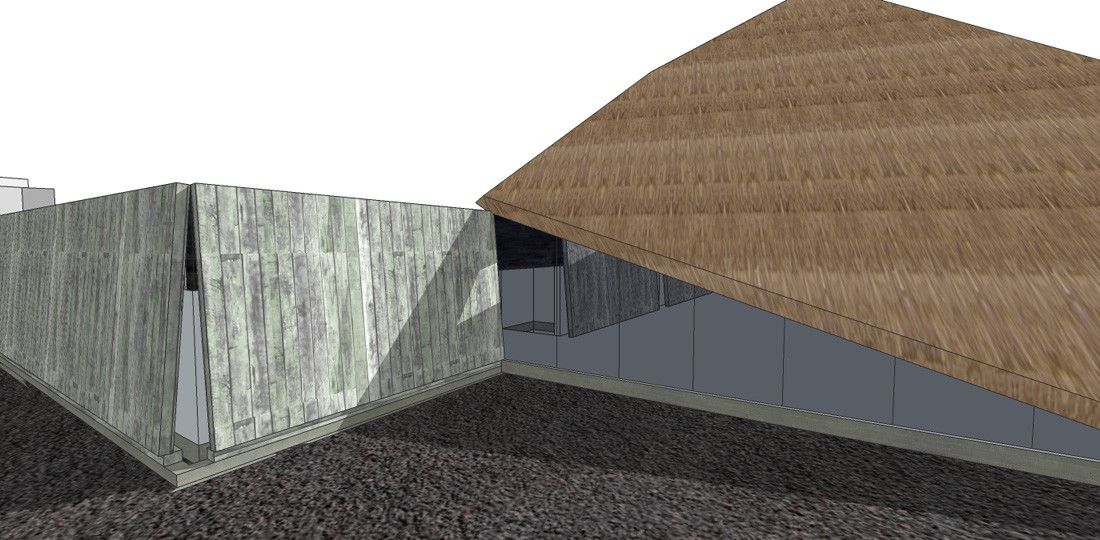

How do we prepare the initial building to grow afterward and still make sense? We thought that a fence was more flexible for future developments than a building. We spent a lot of time trying to balance shape and size for the fence with the maximum space for the workshops but the minimum impact in the context in order to let Hadid’s building be visible from the street.

The long-distance dialogue was followed by a regular face to face meetings with Rolf Fehlbaum and the VITRA crew, where key, very precise and fresh conditions, and orientations were given:

The long-distance dialogue was followed by a regular face to face meetings with Rolf Fehlbaum and the VITRA crew, where key, very precise and fresh conditions, and orientations were given:

Use encouraging materials. Not rough, low budget, but encouraging materials.

Do a happy building. Think of an environmentally friendly eventually recyclable structure. Discipline the form.

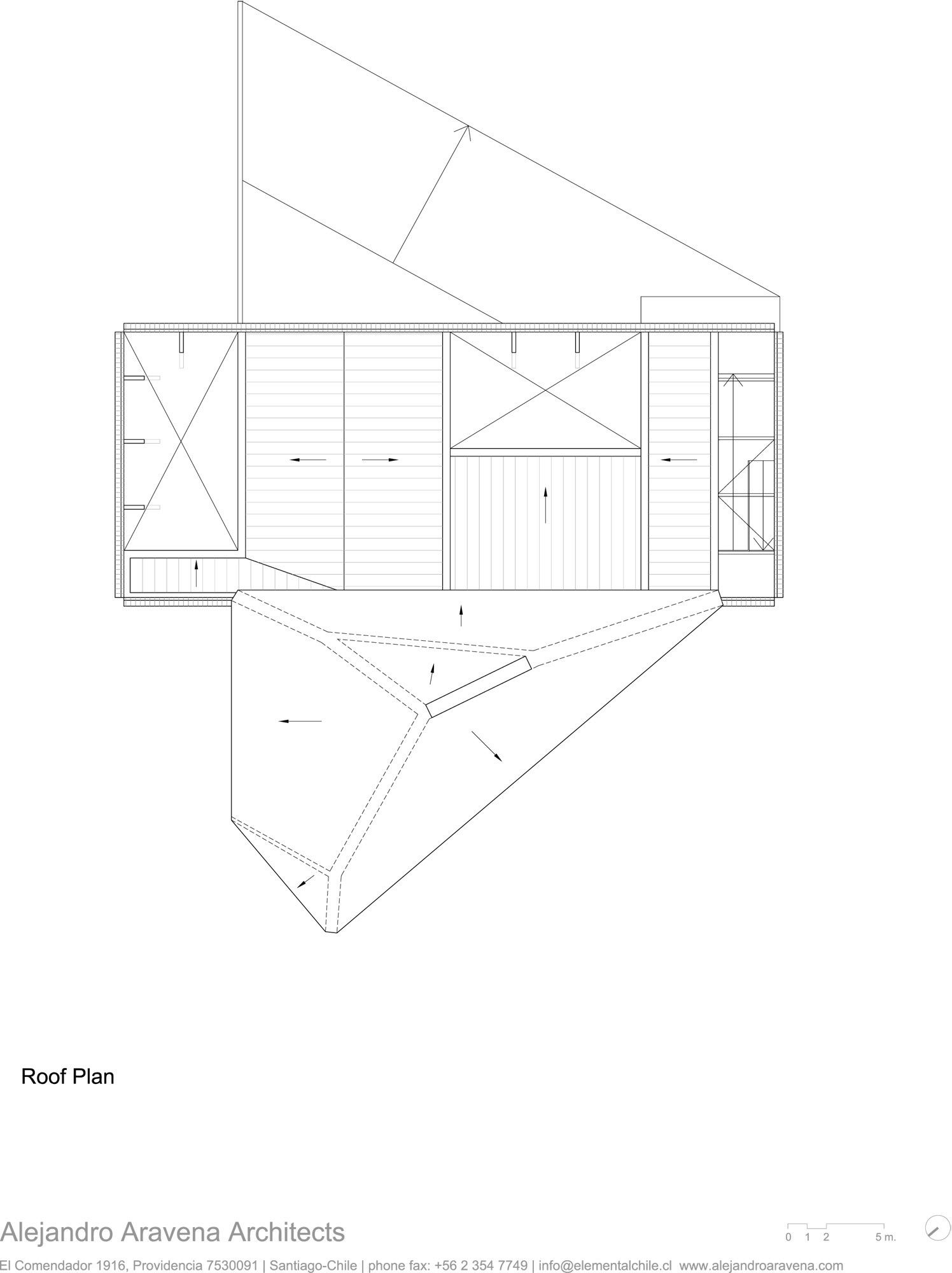

That is how we arrived at the wood and the reet as materials for the building. Form follows facts: The thatch roof follows archaic rules, taken from a time when construction and environment were not an option nor a technique but a fact as natural as gravity. The wood is laid in a way that structural intuition more than calculus informs its form.

Since we cannot compress the time required for an object become a thing, we decided to integrate as many layers of accumulated knowledge as possible, replacing experimentation by synthesis.

Project Info:

Project Info:

Architects: Alejandro Aravena

Location: Zurich, Switzerland

Project Team: Alejandro Aravena + Ricardo Torrejón + Víctor Oddó

Partner Architects In Germany: Osolin Plüss

Models: Ricardo Torrejón

Renders: Víctor Oddó

Area: 600.0 m2

Project Year: 2008

Project Name: Vitra Children Workshop

All Images Courtesy Of Alejandro Aravena

Render

Render

Render

Render

Render

Render

Plan

Plan

Plan

Plan

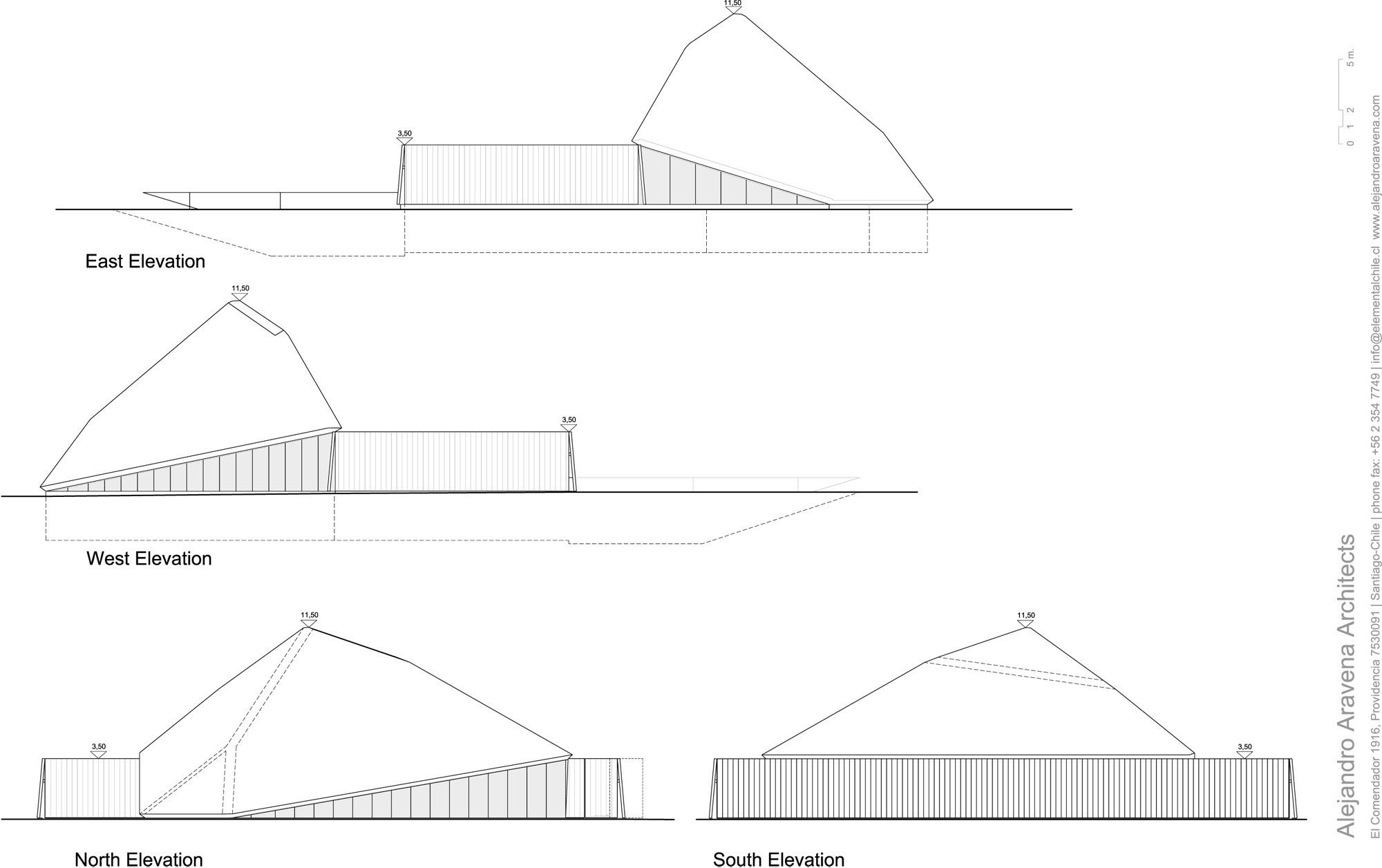

Elevation

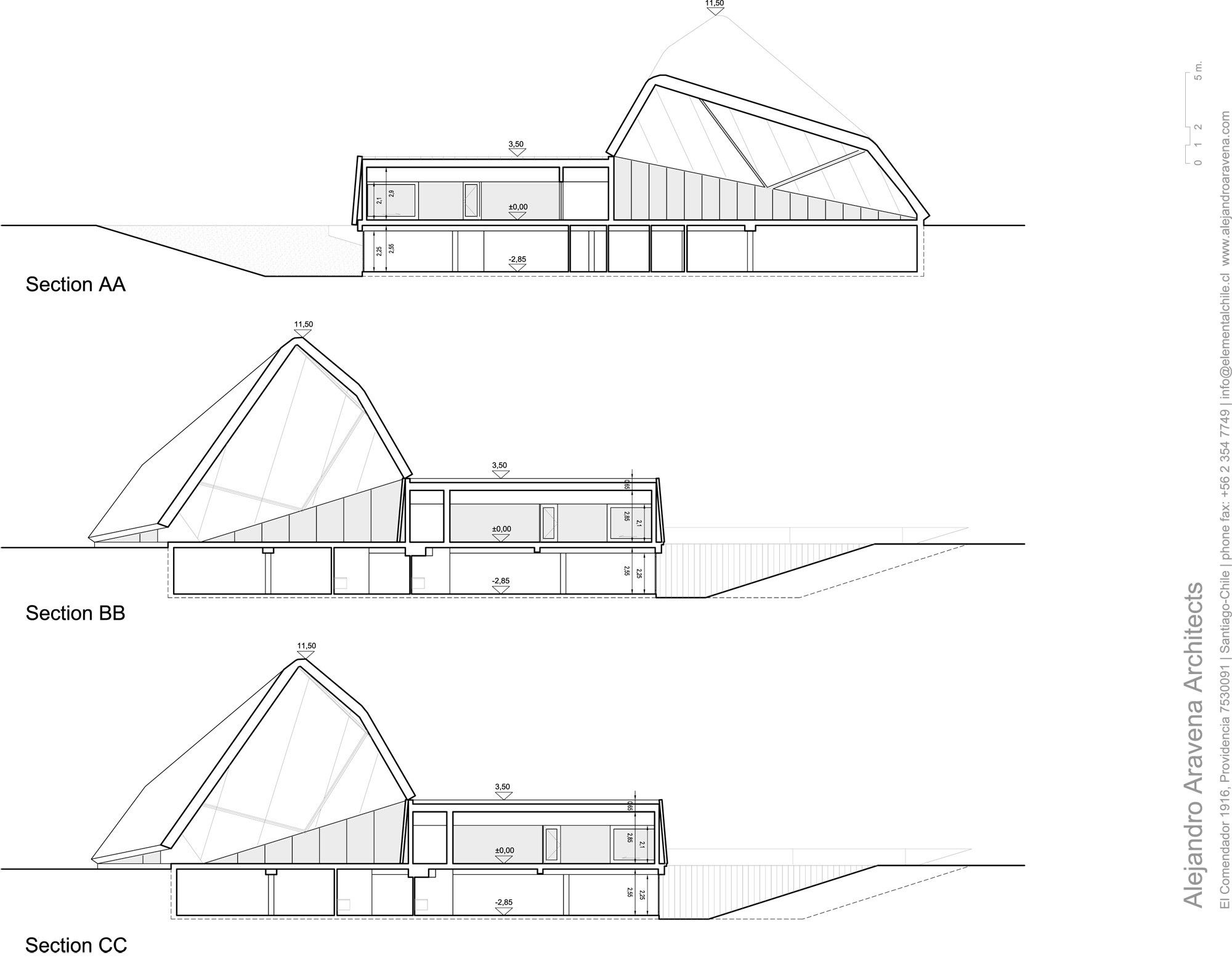

Sections

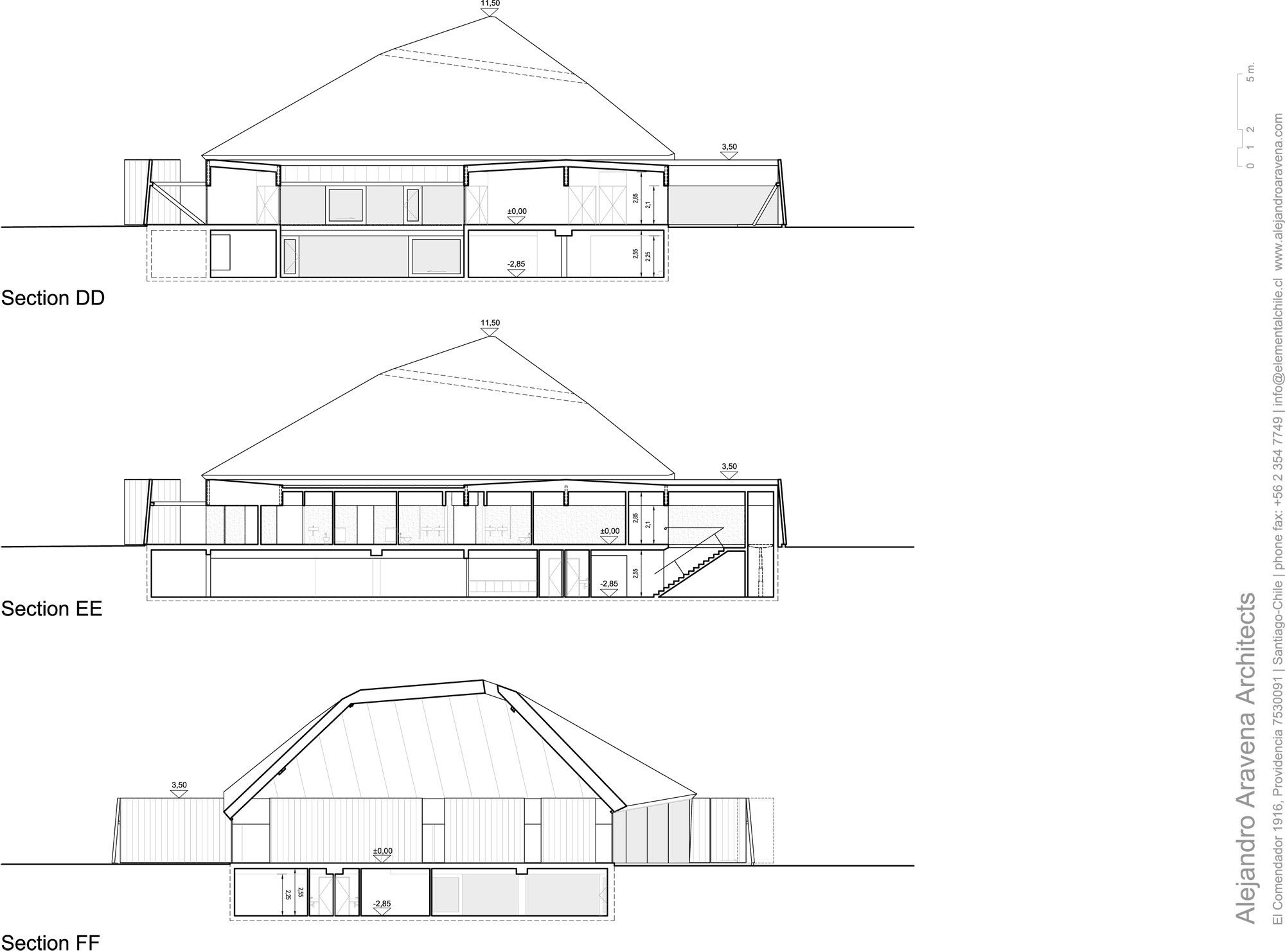

Sections

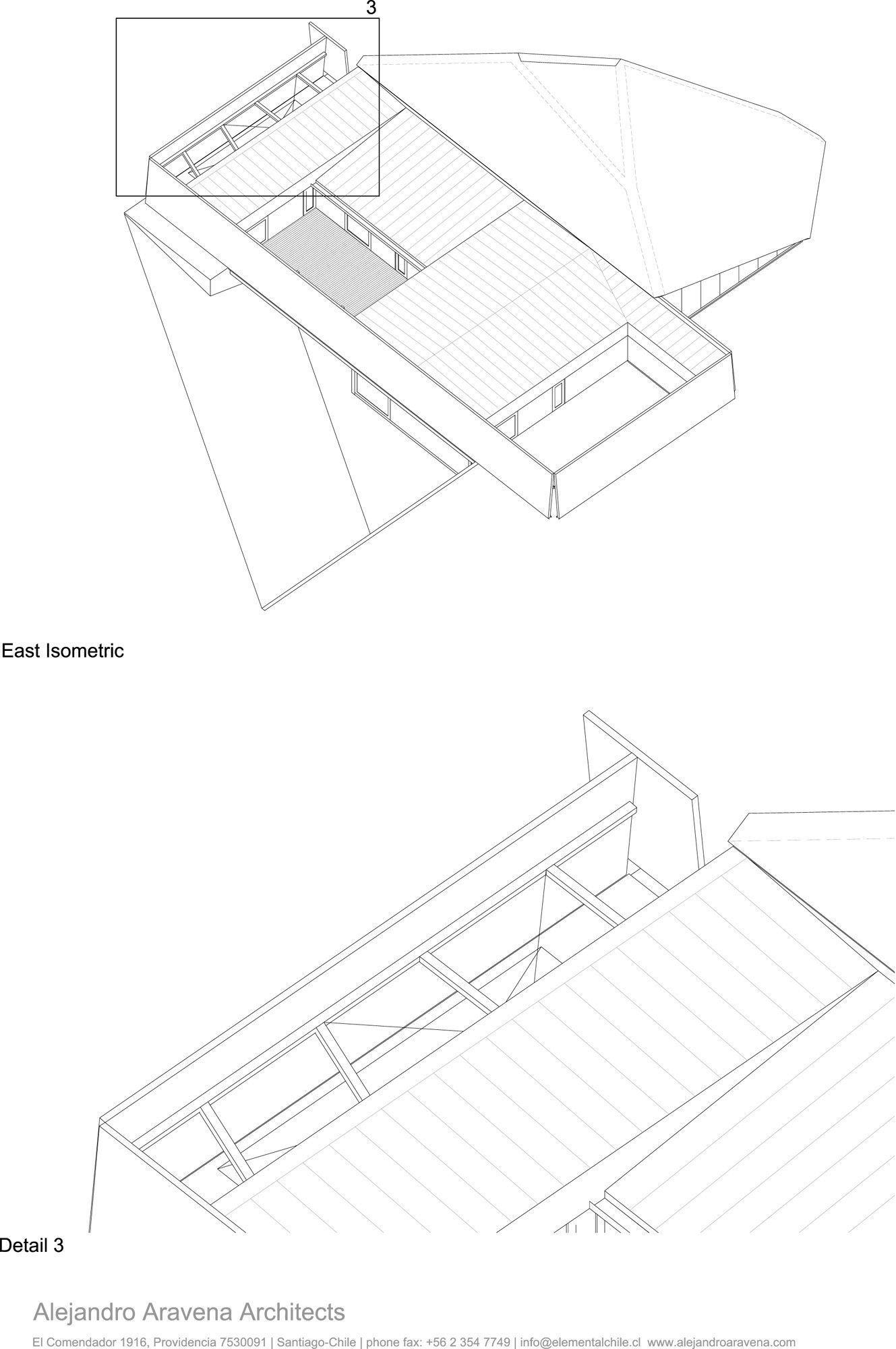

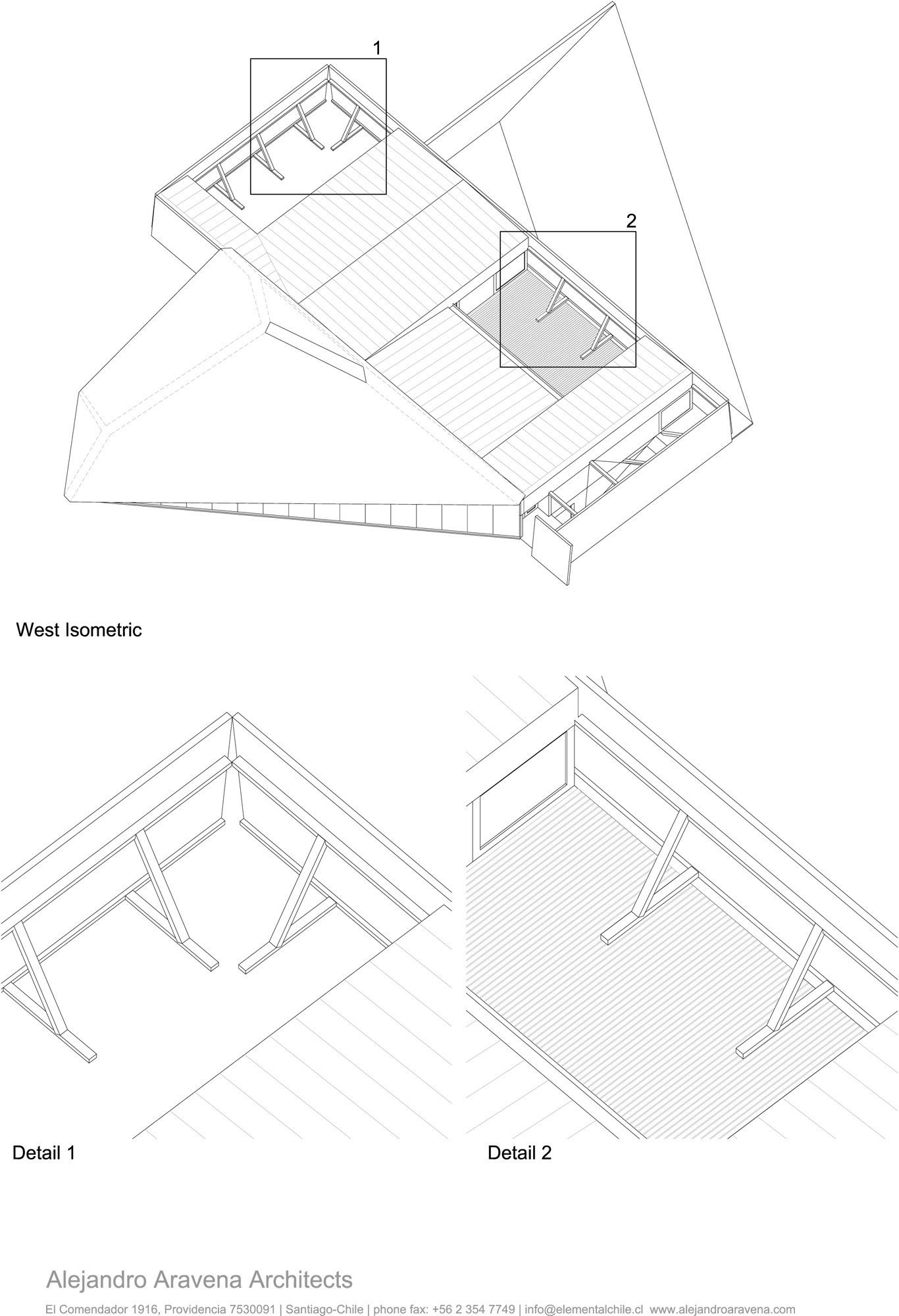

Isometric

Isometric