What the Sydney Opera House could have looked like (7 rejected proposals)

In February 1956 Joseph Cahill – Premier of New South Wales – announced an international competition to build “a National Opera House at Bennelong Point, Sydney.” which is widely known as Sydney Opera House.

The contest allowed architects to enter any number of drawings, as long as they were in black and white. No limit was set on the budget available to build the winning entry. It was pointed out that architects would need to allow space for at least 100 cars to park onsite – mostly those of the orchestra!

So outlandish is winning architect Jørn Utzon’s array of concrete shells, we couldn’t help but wonder what some of the other 222 competition entries might have looked like. So we unearthed seven of the best and brought them to life in this new series of lifelike renderings.

Read more:

The 7 rejected proposals of The Sydney Opera House:

1. Philadelphia Collaborative Group’s Design

Second place in the competition went to this submarine-shaped opera house, created by an improvised team of seven designers in Philadelphia. Like the winning design, the structure was inspired by the seashell form and was to have utilised the latest techniques in the use of concrete.

It may have been pipped at the post, but the Philadelphia team continued to work together after this promising debut, forming the award-winning design group Geddes Brecher Qualls Cunningham (GBQC).

[irp posts=’167693′]

2. Paul Boissevain and Barbara Osmond’s Design

The Dutch-British team’s entry was rather conservative next to Marzella and Utzon’s concrete seashells, which is why it was consigned to third place in the contest.

However, the judges were impressed with the human scale of the building and it’s promenade. And the boxy design and emphasis on walking can’t help but recall the tilted ground-to-roof walkway of Oslo Opera House in Norway, built fifty years after Boissevain and Osmond’s unrealised vision.

3. Sir Eugene Goossen’s Design

Although never entered into the competition the design created by Sir Eugene Goossen could have been realised as the designer held substantial political sway.

Gossen was not only the conductor of the Sydney Symphony Orchestra but also the director of the NSW State Conservatorium of Music and one of the key voices in demanding for an opera house to be built.

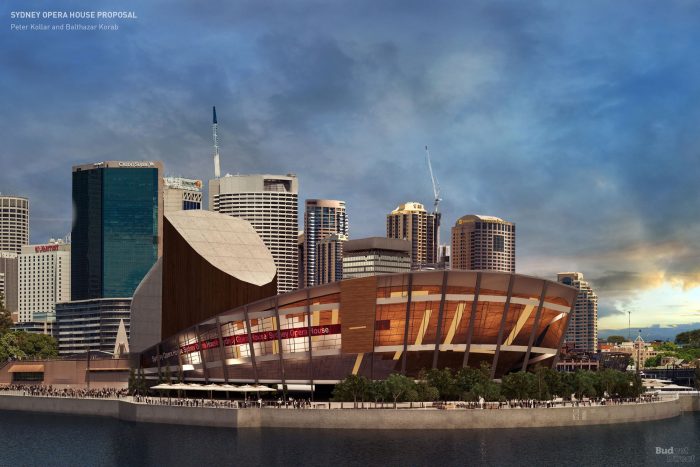

4. Peter Kollar and Balthazar Korab’s Design

Refugees from the communist regime in Hungary, Kollar and Korab’s entry was the highest ranking entry from an Australian entity. The judges commented on the project’s “very skilful planning.”

But coming fourth in the contest didn’t mean the end for Kollar, who had a big part in the ultimately unsuccessful campaign to keep Jørn Utzon in charge of the building project after the Dane fell out with the NSW government.

[irp posts=’283100′]

5. S. W. Milburn and Partners’ Design

Stanley Wayman Milburn and Eric Dow’s design was not so dissimilar from Boissevain and Osmond’s box-shape-with-promenade.

But Milburn and Dow tucked their promenade under the raised building and planted a helicopter pad up on the roof, presumably in case the conductor needed to get somewhere in a hurry.

6. Vine and Vine’s Design

English company Vine and Vine’s sprawling opera house was made up of two auditoria, separated by a restaurant. Like many of their competitors, the Vines made provision for outdoor space – in their case with a sunken waterside plaza.

But two auditoria was one too many for the judges, who consigned the company’s building, complete with vivid red façade, to history.

7. Kelly and Gruzen’s Design

This collaborative group’s entrance echoes the Vines’ with its sunken courtyards. But there’s also a certain Vegas-style pizzazz to the American team’s entry.

Founded in 1932 by Barnett Sumner Gruzen and Colonel Hugh A. Kelly, ‘Kelly and Gruzen’ continues to operate as the IBE Group today.

It took 17 years after the competition for Joseph Cahill’s dream to be completed, and sadly he died in the meantime. But Utzon’s winning entry has become one of the defining symbols of Australian culture, gaining UNESCO World Heritage Site status half a century after the original contest for its design.